Low Cost Border reeds

Jock Agnew has, for some years, been messing around with reeds. It is still very much a hit- and-miss business with him, and whenever he holds a workshop on the subject other peo- ples' attempts seem to turn out better than his own!!

I realise that what I have to say may irritate some of my pipe-making friends. For that I am truly sorry. But it is all about the knotty problem of Border pipe design. These conical chanters seem to throw up more questions than can be satisfactorily answered. The tone, ease of fingering, possibility of a chromatic scale, the ability to pinch up to high B or even further, all seem to depend on a number of variables. And these variables include: the type of wood; the size of the throat; the degree of taper (and the fidelity of that taper); the length of the chanter below the tuning holes or even the very existence of tuning holes. Then of course there are the reeds

There is one piper of my acquaintance who used to play Border pipes. His set, a good- looking set, sits unused on a chair in his living room. He hasn’t picked them up, he tells me, in over twelve months. Why? The reed is broken, and the pipe maker is no longer in busi- ness, so the chanter cannot be sent back for a new reed to be fitted!

There are now (to the best of my knowledge) close on a dozen pipe makers who make Border pipes. Many of them to whom I’ve talked have told me, from time to time, that they have (individually, not collectively) at last solved the problems connected with the Border chanter and all its vagaries. Come back a year later and the story might be that, well, last time they hadn’t got it totally right, but now ! Some have become secretive about the proc-

esses they adopt - a changed scene from 20 years ago when design information on bellows pipes was relatively freely exchanged.

There are various penalties we, as pipers, pay for all this. For instance the fittings on the pipes are not always interchangeable; one maker’s bellows will not necessarily fit another maker’s pipes; the chanters from one maker will not fit into the stock made by another. And (unlike the Highland pipes) the reed that sounds well in one chanter is very unlikely to be suitable for another even though they are both in the same key, and appear identical in measurements and materials.

It has long been common knowledge that Highland pipe chanter reeds can be successfully adapted to the Border chanter. Rather than capitalise on this, many Border pipe makers seem to have chosen to invent their own, to suit each his own particular design of chanter.

And now some pipe-makers are increasing the price of replacement reeds to reflect more accurately the time taken to make them and match them to the chanter. And when the piper needs a replacement he has to return the chanter to that maker - which of course means extra cost and extra time.

Yet there is a supply of free or low cost potential reeds readily available (usually) to the player of Border bagpipes, which may provide a useful stand-by reed or even, on occasion, be better than the original!

Go to your nearest pipe band (or Highland piper even) and you can almost certainly come away with a handful of discarded used reeds. Many of these will be suitable for cutting down for the Border pipe chanter. If you prefer brand new reeds to work with, then High- land bagpipe suppliers will let you sort out suitable candidates, and the cost of these new reeds is relatively modest.

Don’t be alarmed at the prospect of cutting back a reed. It is not as technically difficult as it looks. What I cannot guarantee is that every reed will work in your particular chanter to your entire satisfaction. In my experience the result is unpredictable. I have, over the years, cut back a lot of Highland reeds, and found that with trial and error I can usually select one that will be acceptable (and sometimes one that is excellent) in a conical Border chanter.

And trial-and-error tends to be less painful if the reeds you experiment with are free in the first place!

I should mention that these reeds are more likely to be successful in a chanter designed to take a cane rather than plastic reed.

The reed to be worked on should have certain charac- teristics. If it has already been used in a Highland chanter then there must be clean wood beneath the darkened (sometimes blackened and pitted) surface - an initial scrape with a sharp knife will soon determine this. It should be sound and virtually

air-tight. To check this, stop the end of the reed with a finger and suck at the staple. Very little (if any) air should come through. Usually any leak is down the sides of the reed where the two blades are in contact. If it is only slight it might be mitigated or even cured with glue - more on that below.

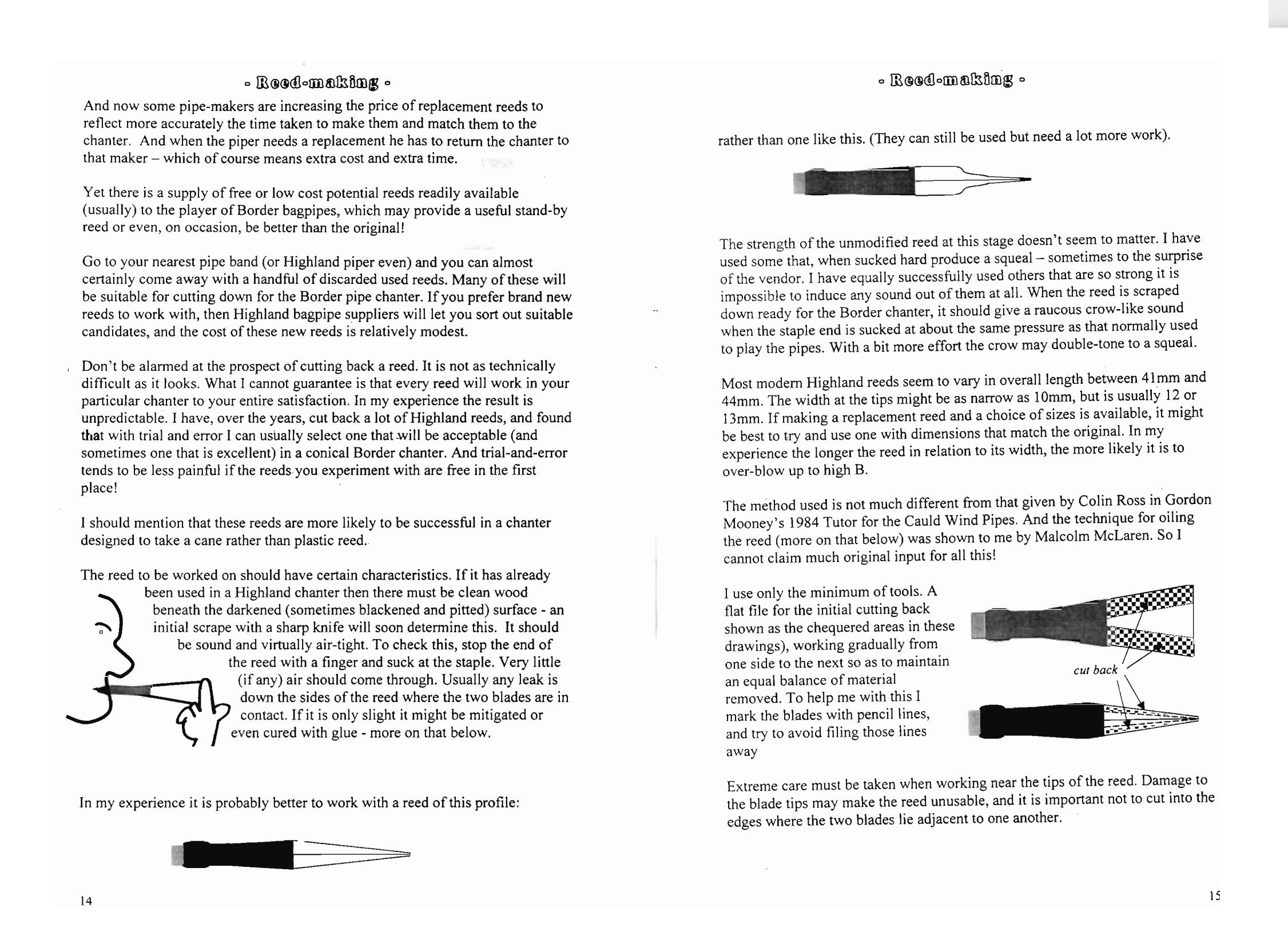

In my experience it is better to work with a reed of this profile:

ather than one like this. (They can still be used but need a lot more work).

The strength of the unmodified reed at this stage doesn’t seem to matter. I have used some that, when sucked hard produce a squeal - sometimes to the surprise of the vendor. I have equally successfully used others that are so strong it is impossible to induce any sound out of them at all. When the reed is scraped down ready for the Border chanter, it should give a raucous crow-like sound when the staple end is sucked at about the same pressure as that normally used to play the pipes. With a bit more effort the crow may double-tone to a squeal.

Most modern Highland reeds seem to vary in overall length between 41mm and 44mm. The width at the tips might be as narrow as 10mm, but is usually 12 or 13mm. If making a re- placement reed and a choice of sizes is available, it might be best to try and use one with dimensions that match the original. In my experience the longer the reed in relation to its width, the more likely it is to over-blow up to high B.

The method used is not much different from that given by Colin Ross in Gordon Mooney’s 1984 Tutor for the Cauld Wind Pipes. And the technique for oiling the reed (more on that below) was shown to me by Malcolm McLaren. So I cannot claim much original input for all this!

I use only the minimum of tools. A flat file for the initial cutting back (shown as the chequered areas in

these drawings), working gradually from one side to the next so as to maintain an equal balance of material removed. To help me with this I mark the blades with pen- cil lines, and try to avoid filing those lines away.

Extreme care must be taken when working near the

tips of the reed. Damage to the blade tips may make the reed unusable, , and it is important not to cut into the edges where the two blades lie adjacent to one another.

This filing process is kept up until I can induce a squeak out of the reed by sucking fairly hard at the staple - protecting my tonsils and lungs by making sure all the wood dust is first blown away.

At this point I start the scrap- ing. Using a flat blade such as a Stanley knife), and holding the reed with a finger to sup- port the blades, I scrape a lit- tle at a time (shaded area in the drawing) on each side. I avoid going closer than about 2mm to the tips, and keep the blade upright on the reed us- ing a sort of rolling motion away from the staple. This

goes on until 1 can suck a fairly strong squeal out of the reed, without having to try so-hard as before.

Now the final scrape. For this I use the small blade of my pen-knife, the cutting edge of which is slightly convex:-

Again supporting the reed from below, I scrape the centre part of each side, frequently hold- ing it up to a bright light to see what sort of translucency is being achieved. I work until a pale area appears (shown in the drawing), making sure that each side is scraped by the same amount.

At this stage it is very important to frequently check the pressure required to make the reed ‘crow’. And I find I have to judge this pressure carefully. For if the lips of the reed are quite open I would expect more pressure (or sook!) to be needed. If they are close together then the pressure used to make it crow should be about the same as normally supplied by bag and bellows when I’m playing in a comfortable and relaxed mood.

This shape will subsequently be controlled, of course, by a wire bridle.

Care is also needed in the area just above the wrapping, (called, by some reed makers, the sound box) which seems very sensitive to any removal of material. I try to avoid scraping this area at all if possible.

Once the reed is making a ‘crow’ at normal playing pressure, I stop scraping, and check for air leaks (see Pge 8). If when sucking against the stopped end I lose vacuum to any notice- able extent, I apply a thin line of white wood glue up the edges where both blades meet.

This is smoothed in with a finger and any excess wiped off. Finally I apply a mixture of neatsfoot oil and white spirit (in 50/50 proportions) to the outside of the reed blades and to the joint between blades (if not glued). This I work in well with finger and thumb, then leave it for a few minutes to dry.

The use of oil seems to make the tone more mellow, and reduces the effect that changes in humidity-might have. It may also marginally lower the pitch. And if we think about it there is a certain logic, for if the reed had pursued a different career (in the Highland chanter, for instance) it would have spent a large part of its life in a moist condition.

With the reed relatively dry, I check again for the crowing sound (remembering that the air sucked in will now smell/taste of white spirit and neatsfoot oil). At this point there may be the need to scrape a tiny amount more off the flat of the blades to get the reed to crow at the same pressure as before.

Now the final stage, the bridle. I’m not convinced that type or size or wire is vital. If it is copper wire it may leave green marks, if it is steel it may leave rusty marks, but who is go- ing to peer inside your chanter? The heavier the gauge the fewer turns you will need to maintain the control of the blades, for after all it is only put on for that purpose. I use two turns of 25 thou diameter steel wire, because I happen to have a reel of the stuff. I have suc- cessfully used those plastic covered wire tags that come with bin liners when three or four

turns are necessary to gain the control. The best position seems to be well down the blades, next to the wrapping.

The blade tips are closed to the right aperture by squeezing the middle of the bridle with a pair of pliers. Don’t overdo it. The staple underneath is also being flattened slightly, and is rather difficult to open up again later if required. The final (minute) adjustments I do with my fingers, gently squeezing or opening the blades once the reed has been tried in the chanter.

So, the advantages are; a cheap, maybe free, reed, one that can be blown with the mouth without feeling guilty! and the hard part having already been done by the reed-maker. And the disadvantages? Well, the unpredictability - several reeds may have to be made before one suits your chanter, and the time taken to scrape one down - although I find I become quicker with practice.

JA