LBPS Collogue 2004

It was held at the College of Piping, newly re-built, freshly decorated. About 30 of us attended this annual event, and were glad we did. The line-up was impressive: Rab Wallace with a couple of members of the Whistlebinkies; Paul Warren with members of the National Youth Pipe Band of Scotland; Richard Butler with pipes and regalia as the Piper to the Duke of Northumberland; and Jean-Pierre Rasle with a clutch of French bagpipes and bells.

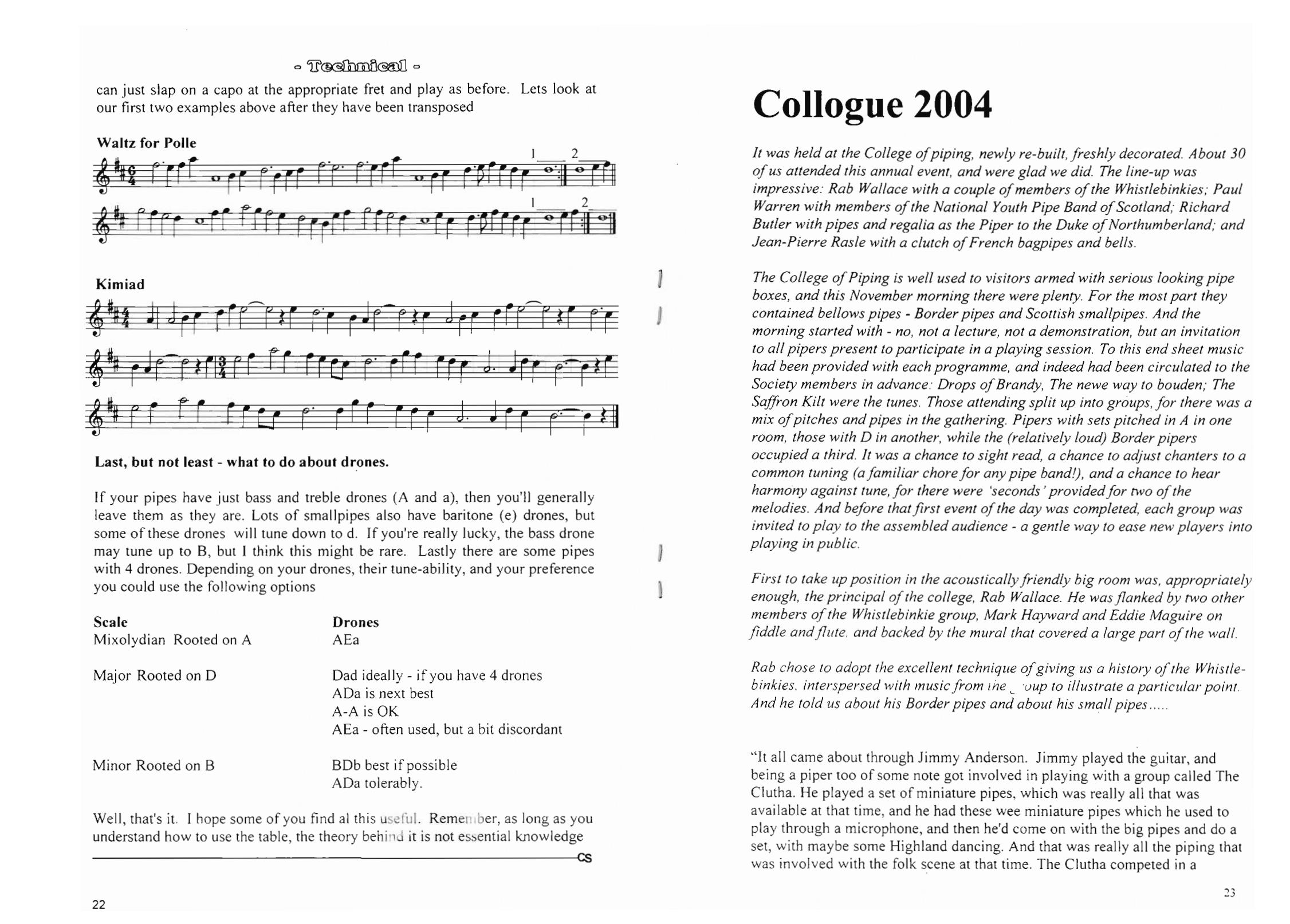

The College of Piping is well used to visitors armed with serious looking pipe boxes, and this November morning there were plenty. For the most part they contained bellows pipes - Border pipes and Scottish smallpipes. And the morning started with - no, not a lecture, not a demonstration, but an invitation to all pipers present to participate in a playing session. To this end sheet music had been provided with each programme, and indeed had been circu- lated to the Society members in advance: Drops of Brandy, The Newe way to Bouden; The Saffron Kilt were the tunes. Those attending split up into groups, for there was a mix of pitches and pipes in the gathering. Pipers with sets pitched in A in one room, those with D in another, while the (relatively loud) Border pipers occupied a third. It was a chance to sight read, a chance to adjust chanters to a common tuning (a familiar chore for any pipe band!), and a chance to hear harmony against tune, for there were ‘seconds’ provided for two of the melodies. And before that first event of the day was completed, each group was invited to play to the assembled audience - a gentle way to ease new players into playing in public.

First to take up position in the acoustically friendly big room was, appropriately enough, the principal of the college, Rab Wallace. He was flanked by two other members of the Whistlebinkies group, Mark Hayward and Eddie Maguire on fiddle and flute, and backed by the mural that covered a large part of the wall.

Rab chose to adopt the excellent technique of giving us a history of the Whistle-binkies, interspersed with music from the group to illustrate a particular point. And he told us about his Border pipes and about his small pipes......

“It all came about through Jimmy Anderson. Jimmy played the guitar, and being a piper too of some note got involved in playing with a group called The Clutha. He played a set of miniature pipes, which was really all that was available at that time, and he had these wee miniature pipes which he used to play through a microphone, and then he’d come on with the big pipes and do a set, with maybe some Highland dancing. And that was really all the piping that was involved with the folk scene at that time. The Clutha competed in a tradi- tional music group competition festival a couple of times, they kind of took things on in that basis. But it really wasn’t satisfactory sound-wise from the piper’s point of view.

Jimmy was a joiner, and he was forever cutting his fingers and sawing off the tops of his nails and one thing and another as you do if you’re a joiner. He asked me once to stand in for him for a gig up in St Andrews, so I did the same thing “

“As a joiner or as a piper?” [The interruption came from Eddie Maguire]

“Very good, very droll, now I’ve lost the thread ! I stood in for Jimmy, and he came along

and supervised and made sure I did things properly. And so I went along to some of the fes- tivals, and it was a kind of opening because of course I was away from the piping thing, the bands and the solo piping world. It was all very strict and serious, but I found playing in the folk scene the audience was a positive audience, they were more looking to hear you play and enjoy themselves than listening for mistakes as often you get in the piping world. At that point I met one or two of the members of the Whistlebinkies, which had been going since, what, 1969?” “Round about then.” [from Eddie], “And they were looking for a piper following the Clutha’s lead, they thought there was something worth doing here, and they asked me to join them which I did in 1974. And that’s thirty years ago...........

“Then what we did was the same as Clutha - got a set of miniature pipes made by Bob Hardie - but it was never satisfactory - I was never happy with that, because these boys [Rab nods towards Eddie and Mark] were louder than I was, and I wasn’t too pleased about that. I was up at Inverness that year, at the Folk Festival, and I went into the museum and I think Francis Collinson’s book had come out about the same time, and this was a revelation, because none of us had ever heard of Lowland pipes. And I thought it would be great if I could get a set of these Lowland pipes. Up at the museum in Inverness we got drawings and we went back, and the idea was to get a set of these things going - because nobody made them at that time. I had bought a set of half Highland pipes and they matched exactly the drawings of the Lowland pipes we got at Inverness museum. All we needed was a common stock and big Iain MacDonald of the Neilson Band whom you all know and love, well his father-in-law worked at the Rolls Royce factory so he turned me down a barrel of wood with three holes in it, and I stuck the drones of the half set pipes into this barrel stock and found smallish Highland cane pipe reeds - they worked just fine. I got a set of bellows made by David Burleigh, the Northumbrian pipe-maker, with extra capacity in the bellows, and after 3 or 4 months I began to get some semblance of a sound out of the thing. Once I had done that we launched it on the unsuspecting public! Very much a kind of hybrid set of Lowland pipes. We were asked to do a track on a Hamish Henderson album, which I hope is still available, the track was called The Banks of Sicily - we’re going to play that now.

“You’ll notice I only ever use two drones on these, because at concerts you really must be tuning up during the applause ready to go into the next number. There’s no time for the E drone and getting it all spot on, so I’ve just got into the habit of using two drones.

“At the recording that we did there was a man called Gareth Brown, who was the proprietor of Claddagh records in Dublin, and once he’d heard us he asked us if we’d like to do a re- cord, and we got a contract from them at that point (he must have been impressed with my haircut or something!). I should say something about the pipes but before I do that we’ll play our next number. This was the very first track that we recorded using the Lowland pipes - a special arrangement made by Eddie here to Duncan Johnston’s well known tune called Farewell to Nigg.

“About that time I was involved with Grainger and Campbell, and I got the pipe-maker there to try and copy a set from the drawings I told you about earlier. He did so, and that’s the set I’m playing today. He also made a chanter, but I found the chanter didn’t make as good a sound as the one I had, and so I just kept playing that one. So in reality this is just a half size chanter made by MacDougal of Aberfeldy, with the same bore as the Lowland chanter drawings that we had. I’m sure these weren’t standardised, they all varied. And it’s all taped up to hell as you can see. We always went for Bb, because it is easier to get up to Bb than to get down to A. (It’s actually pitched halfway between them, this chanter). The other reason for going Bb was the clarsach. It makes it difficult for the flute and the fiddle, but who cares about that! There are various ways round it, as Eddie will explain. The Shet- land music we played at the start, is slightly off the pipe range, but with a bit of judicious arrangement you can get most of the notes and get a good approach, which with a group

like this, with good arrangers like Mark and Eddie you can broaden the repertoire of the nine notes quite considerably - with a bit of thought and good musicianship. So I think that is a good introduction to Eddie Maguire who has really managed to arrange all this stuff for pipes over the years - one of the reasons why it has worked so well with pipes and other in- struments.”

[Eddie takes over] “I think also, right from the start of the group, we have all tried to write original tunes, and keep the creative spirit alive in the group. It is a living tradition, after all. So I think nearly every member of the group has written his or her own dance tunes and slow airs and other pieces to expand the repertoire of the group, and especially to integrate the instruments into it. It is team work rather than solo work, that we are engaged in. So a lot of the instruments are contingent to a lot of harmony work, inner parts and all that kind of thing. It is a matter of getting the Lowland pipes well integrated into a group context. So as Rab says, for some reason over the last 100 years the natural key of the average clarsach has been in three flats [Eb]. I’m not sure what the origin of that was, it might just have been the best resonance for that size of instrument or something. Some players these days tune in

G. In Northumbria, the clarsach society there I notice tune in mainly C and G. But the main- stream clarsach societies throughout Britain and America tune their instruments in 3 flats. In our group we add one more flat, and Rona and Judith Peacock used to - still do - tune their clarsachs in four flats [Ab]. So it means the fiddlers and flute players have to learn all the tunes in flat keys. So that’s why it is difficult for us to sit in sessions in pubs, and play with the normal average fiddler who is playing in D and G, because we know all those tunes in Ab and Bb. I think it’s a plot to keep the Whistlebinkies out of the pub! Nevertheless the fiddlers in the group have got the trick of having two fiddles - you have a double fiddle case with you - and one is in normal pitch, and can play easily in D and G, i.e., other fiddle is tuned up a semi-tone, so that with the same fingering it can play in flat keys of these Low- land pipes. I use the keyed flute. I get a bit more power - the piccolo blends well with the Lowland pipes. The viola as well, we use in the group. So we make a feature of arranging and writing for the three national instruments of Scotland; the fiddle, the clarsach and the pipes. Our logo - which you see on the records - was used on the Whistlebinkie poetry book in 1832. So we try to keep that tradition going as well. The original music we wrote is probably best illustrated by a piece I wrote for the Scottish National Orchestra chorus - there are about a hundred of them singing in that, and obviously the great problem for an arranger or a composer is the volume of the pipes. They are unchangeable, but you can ad- just it by the intensity of grace-notes or the music itself.. So I thought a great way of doing this would be to employ three different types of pipes with the choir. For the very hushed voices at the beginning and the end Rab played the small pipes with its D drone and in the key of G on the chanter. That blended nicely with the hushed voices of the choir. Then as the piece grew into intensity, Rab changed to these Lowland pipes which are a great notch up in volume. Then he went onto the Highland pipes for the climax of the piece, then as it wound down, back to the Lowland pipes again and then at the end with the quiet voice of Kathleen MacDonald it went back down to small pipes. So that’s a way of controlling the volume with three types of pipes. We’ll play some more music now...”

“In 1986 there was a milestone in our history of the Whistiebinkies” [Rab again] “when we appeared on the front cover of the Lowland and Border Pipers’ society magazine [Vol 3 No 1 - and you’ve done it again now!!!]. That was the piece that brought together bombard, small pipes, Lowland pipes, Highland pipes and clarsach - it was quite an extravagance.

I’ve always had a very loose approach to what I actually play on these pipes. And obviously coming from a Highland pipe tradition that’s where you are coming from. But I don’t sub- scribe to the view that you have to play that stuff [Highland pipe music] on these pipes. I think you can play just about anything on them. Some things - bits of vibrato - lots of grace note or no grace notes - it all comes down to what you like yourself, your musicianship and your musicality. Too many grace notes can spoil a tune sometimes, other tunes are quite ap- propriate to them in. I’ve never really worried whether I was conforming to any particular style. The best approach is just to play the damn things. Early on the Lowland pipes, weren’t too popular. I think the Society has maybe touched on that in various articles. The emphasis, the kind of direction, was always towards the small pipes. These are a bit more difficult to play, there’s no question about it; the Lowland pipes are more difficult. But the makers like Nigel [Nigel Richard - in the audience] and others are easing the path. I think the Lowland pipes have definitely got a place because in terms of projection for concerts they are clearly better than the small pipes. If you play in A on the small pipes the fiddles are an octave higher and will carry far better than you will. You are always kind of rumbling away in the background in an acoustic sense. The Lowland pipes - the Border pipes - you’ve got that projection, you are up there along with the fiddler who can play strongly, play well. Not much difference in acoustic balance. So we’ve always liked this instrument. We’ve done concerts in biggish halls without any microphones - we try not to use micro- phones if we can possibly avoid it. It usually works quite well. Occasionally there’s an acoustic where the pipes are flung very loud - a little like it is in here. Occasionally you will find that, in which case I’ll maybe try and find a bit of carpet or something to play on or I’ll move to the back of a semi-circle and let the other instruments come more to the front so that the audience is getting as close as it can to some sort of natural acoustic balance - but that's just a wee bit of trial and error before the gig.

“As the small pipes came onto the scene, Jimmy Anderson made me a set, and we got them into the group. The good thing about the small pipes was they had the natural keys for eve- ryone to play along with, they were good for singing with as well.

“I’ve played the reed in this [Lowland pipe] chanter for 30 years now. That’s the same reed that I used when I first got this chanter going - and I’m feared of looking at it! Every gig I go to I just blow them up so I leave them. I’ve got a poly-bag round the actual bag here - just to keep some moisture in them. I find that helps, especially if you go to a dry country or are playing in a dry atmosphere. I try never to season them, because that upsets them as well. So I avoid that like the plague. If you’ve got a good bag, a good hide bag, it doesn't take a lot of seasoning anyway. If you put seasoning in them it takes them a wee while to settle down after that. The drone reeds -I think I’ve changed them once in 30 years.

“Simple cane reeds with a bridle - a waxed bridle. Once you get them set, that should be it. The pressure you can achieve with the bellows is nothing like the pressure you have with your mouth which I think is about a pound and a half per square inch. The bellows pipes are a lot less than that, so you’ve got to engineer those reeds to get them down, get them easy enough to play, so that they take the minimum amount of air and you can get through your pieces with a degree of comfort. The other thing I have always tried to do is to keep them in tune. Because there is nothing worse than not being in pitch. I think it is wrong to be a slave to some sort of theory that they were meant to be in this key or that they were meant to be in the pentatonic, mixolydian or whatever. I just go by what sounds good. And of course these guys [other musicians] keep you right, because if you play with musicians like Eddie and Mark then you have to be on the right pitch or you are not going to sound very good.

“We also have a concertina in the group which is fixed [the tuning] so we have to work with that as well. The problem with having the clarsach is that the pipes, as you warm up, they go sharp, whereas the clarsach strings stretch and they go flat. Sometimes you can have a wee bit of a problem with the tuning. But I would recommend the Lowland pipes to all of you who play small pipes. It’s not that great a leap to play them, and good business for Nigel and the other makers!

“I really think all bellows pipes players should play both instruments. If one is more diffi- cult there is no reason why you shouldn’t play nice easy simple tunes on them. Being in A they are a more accommodating key, and you don’t have the problems that Eddie and Mark have. So we’re going to play a couple of tunes now.

“It is hard to imagine that when you go back in time there was absolutely nothing - the pipes and the folk tradition just did not talk to each other. And I think it is a great credit to this Society [LBPS] that that has been turned round. And it’s hard to find a Scottish tradi- tional music group today that doesn’t have pipes in it. And it’s usually bellows pipes. I think that is great credit to all the people who formed this Society, took the thing on. People like Hamish, Gordon Mooney and all the rest. So well done you.

“We’ll finish with a wee set on the smallpipes.”

NATIONAL YOUTH PIPE BAND OF SCOTLAND.

Paul Warren, talked about The National Youth Pipe Band of Scotland, of which he is Direc- tor. “A great job, one I’m really proud to have.”

“What exactly is the National Youth Pipe Band? It’s a non-competing band first of all, and it’s very important that I stress that. And it draws its young pipers and drummers, hopefully some of the best young pipers and drummers, from all over the country - it’s certainly not a central belt [of Scotland] focussed operation; something we really want to be sure about.

Our aim is just to promote young people into playing our music, hopefully in the longer term to a wider audience.”

Paul went on to say that “Part of the organisation is getting young pipers and drummers to actually speak and engage with their audience.”

And to illustrate this point he invited members of the band to step up and give a short presentation of the band, and how it looked from their point of view.

Paul described some of their philosophy towards the music they played: “... choose music that stands up - not just in front of a piping audience ... [and] ... to have credibility [they] must be able to perform in front of a critical piping audience (most piping audiences are!), but we have to take our music and actually make it stand up and entertain perhaps a non- piping audience.”

Several of the young pipers and drummers are writing their own tunes and individual arrangements, and we, the audience in the College of Piping, were treated to some of the results.

“They don’t have any regular practices,” Paul Warren went on, “so they have to get every- thing together when they meet up. So I just say ‘You are pipe major. You are pipe sergeant - make it happen’ and leave it to them. Get them to engage with an audience, get them to compose, identify players of other instruments, be more involved in concert production. A third of the membership is female - it wasn’t intended, it just happened”

They have already toured abroad, and been to China and to Spain.

Mike Paterson, who was closely involved in the feasibility study that led to the forming of the band gave an insight into the decision making process. “Critical to its success it needed someone competent to direct it - work with young, pipers, musicians, teachers, schools. Just over a year old the achievements have been formidable. These kids are putting piping right into the limelight.

THE DUCAL PIPERS OF ALNWICK CASTLE

Richard Butler is the current Piper to the Duke of Northumberland, a post which he has held since 1982. He started bv playing Chevy Chase on his 18-keyed Northumbrian smallpipes.

“That was Chevy Chase, and whenever I play for the Duke of Northumberland he asks for Chevy Chase. If you know the history of the battle of Chevy Chase, it was basically a little altercation between the Percys and Douglas in the 12th century.

“I’ll [describe later] how I fill the role of the Duke’s Piper in the present day, but I’ll go back in history in terms of when it actually started, and what happened from 1766.

“At the beginning of the 1700s, we had roving musicians, people who made money out of going to fairs and playing and performing, etc. We also had the town waits - people em- ployed by the town council to go round as musicians and tell you what time it was; so they’d come out at ten o’clock at night and say “It is Ten O’clock” and play a few tunes. They would wander around Tyne-side, and Alnwick - all theses places - as Town waits. And they were actually paid by the council to do this. There are a lot of references to the Town waits. But also we have the nobility, people like the Percy family in Alnwick. They had musicians. Amongst the musicians they also had pipers. So we had the gentry as sponsors of music. And we also had the militia who had their musicians. So at the beginning of the 1700s we had all these groups of people for various reasons playing different instruments.

“The first reference we come across to the pipers to the Dukes of Northumberland or Duchess of Northumberland is actually in a book called The Life of James Allan. Now James Allan was a bit of a coloured character - a gypsy born in Rothbury. And knowing gypsies and knowing these colourful characters I think they embellished the stories. But his book, which was written at the beginning of the 19th century (not by James Allan) is obvi- ously a history of his life. But I think you’ve got to take a lot of it with a pinch of salt, be- cause he did some absolutely fantastic things. But having said that, it does make a reference that in 1746 /47 he actually played for the Duchess of Northumberland. Well that’s wrong to begin with, because the Dukedom didn’t come into existence until 1766. So he actually would have been playing for the Countess. So that is the first reference we get. And if you look at the history of Alnwick in 1752 there is reference to pipers being present with the other musicians. Now I was actually at the castle on Monday night playing for the Duke - I’ll tell you about that in a minute - and the Duke has a very nice portrait of Joseph Turnbull, and the inscription at the bottom says Piper to the Duchess of Northumberland 1756. Well that’s wrong again. It can’t be the Duchess, because [as I said] the Dukedom didn’t come into being until 1766. But that portrait was painted in 1756, and some time after 1766 that title was put on the bottom. So now we have a reference to pipers officially being in place in the castle. Before 1766, James Allan accompanied the Countess to the coronation of George III, and whether in fact he was an official piper in that respect I don’t know. James Allan clearly had some kind of influence with the Duchess, which becomes

more apparent a bit later in his life. At this time the Duchess presented James Allan with an ivory set of pipes. So there was this connection clearly being established. Now who was the

first Duchess’s or Duke’s piper? Honestly I don’t know. It could have been James Allan, it could have been Joseph Turnbull. We don’t know. But in 1766 we have the Dukedom being created, centred in Alnwick. Also in 1766 there is another reference to James Allan, in his own book I might add. Not written until the beginning of the 19th century. It talks about wearing the Percy crest. If you go around Northum- berland you can see this above doorways in estates owned by Alnwick. The Duke’s pipers have always worn that as a badge on the left arm. And this one [displayed] was handed down to me. I also have it on my hats badge - and I wear a plaid as well.

‘ So what we‘ve got now, in 1766 we have actually the Duchess’s official piper (the first head of the Dukedom was actually a Duchess). Who was piper to the Duchess at this time? I would hazard a guess it was

Joseph Turnbull, but James Allan no doubt had some influence and turned up from time to time.

‘ Just after 1766 our colourful character, James Allan, was one of the town waits of Alnwick; he was enrolled into the militia; and he was actually playing at the castle. Then he was caught stealing and thieving and was dismissed from all of them. So he kind of fell out of favour a bit there.

“The next time we come across the Duke’s Piper actually being appointed is in 1780, a guy called William Lamshaw. There were two William Lamshaws. And depending on which book you read it was the grandson or the nephew. Both called William Lamshaw, but not father and son. In essence they were actually employed by the castle, by the estates. We believe as musicians, we don’t know whether they were solo musicians, but basically they were employed by the castle to come round and play whenever the Duke required. Exactly what the Lamshaws did we can only surmise, but I expect they also played at functions requested by the Duke.

“I’ll play Lamshaw’s Fancy.

“In 1803 James Allan died in Durham Jail, accused of horse stealing. And because of his

age he wasn’t deported and he wasn’t hung which was the more normal sentence for horse stealing, and he actually received a royal pardon signed by the Prince Regent. Now if you think about that - you’ve got a guy from Rothbury in Durham Jail, a gypsy, accused of horse stealing, he’s a deserter from the army etc etc, but he got a royal pardon: He had contacts, this guy did! It had to be the Duchess who got him that pardon - no shadow of a doubt. But sadly the pardon arrived two days after he’d died, and he lies buried in Durham Jail. I’ll play Jimmy Allan.

“Coming now into the beginning of the 19th century, and the next piper appointed was a guy called William Green. It was at this time that the title ‘Piper to the Duchess’ changed to ‘Piper to the Duke’. He started to refer to himself as ‘Piper to the Duke’. When I received my letter it actually came from the Duke, it didn’t come from the Duchess. And also if you look at this period, the 19th century, you need to appreciate just what was happening in Northumberland and to society in general. We’ve now got set up The Ancient Melodies committee by the Duke to collect all the ancient melodies in the area to prevent them being lost - like Bruce and Stokoe, Northumberland Minstrely, etc. So at this time people are starting to take an interest in the pipes away from the people like Jimmy Allan who were basically the gypsy roving musician, itinerant musician. The pipes are coming into the hands of the middle classes. And in 1857 you start to get a situation where ancient melodies committees are going around collecting all the tunes and saying let’s promote the music a little bit more. And James Reid of North Shields piping fraternity gentry pipe-makers, start to take an interest. And we’ve got another piper - so we’ve actually got two Duke’s Pipers at this particular point in time. Why we don’t have two Duke’s pipers now, why it wasn’t con- tinued, I don’t know. There was just a little bit of a blip, things were going down, and they said why don’t we get more people involved with it. So at that point we had a Duke’s Piper and a deputy Duke’s Piper.

“As time goes by now we end up with a situation with pipers starting not only to be clearly distinctly realised in the castle as people in their own right, but the musicians start to disap- pear as well. So we eventually just end up with one piper. If you look at Tom Green he was being paid £30 to go round all the fairs and functions in Northumberland and perform as a piper. And he’d turn up at a fair and he’d turn up at a court and he’d play his pipes. I don’t think he had any other duties apart from that. So there was only the one musician left at the castle. At the same time, thinking of the social change taking place, you’ve got the reduc- tion in cattle being driven down from the Borders into the markets and all the fairs that pipers played at started to be disbanded, and as all the fairs started to disappear the Dukes pipers started to diminish. I used to live in Rothbury and the whole of the howff I have been told used to be covered by the fair. Cattle were driven down, and the Duke’s piper would play at that. A lot of the social interaction disappeared.

“By the time Tom Green passed away we had come to a situation where James Hall is tak- ing over, then in 1930 it was James Byrnes. James Byrnes was a person who was actually working at the castle, so in essence was not a full time musician. He was actually the Gate-

man of the castle, having worked in the Northumberland militia. So he was basically in the position of being employed by the castle but he happened to play the pipes at the same time. So we’ve moved now from a situation where there is a musician going around representing the Duke at fairs, courts etc, to a situation where the Duke’s piper is employed by the castle to do other things but he happens to play the pipes as well. Then in 1949 when he retires, the Duke’s piper is appointed from outside the castle. In essence, Jack Armstrong who came in in 1949 was the first piper to be appointed on an honorary basis; to keep the tradition go- ing. So at that point we could have actually lost the Duke’s piper. Jack Armstrong (who taught me) took it as an honorary position, and Tom Mathews took it over as an honorary position as well.

“I’ll play you a tune written by Jack Armstrong. He not only played the pipes, he made them as well, and he ran a group called the Northumbrian Barnstormers. So, Rothbury Hills by Jack Armstrong.

“So Jack, Tom and myself were the first honorary pipers. People ask how do you actually become the Duke’s Piper - it’s simple; the Duke asks you! The Duke uses certain criteria I think - like you’ve got to be able to play the pipes!! But the Duke wants somebody who can actually stand up and play at some very very important functions. The first function I played at was in front of the Queen. I stood there at Alnwick castle with my badges on and played for Her majesty. You need somebody who can be in that situation - walk in, play, and walk out. I played at the 10th Duke’s funeral at Westminster Abbey (the only family that has any rights, by the way, to be buried at Westminster Abbey are the Dukes of Northumberland).

Just behind the altar at Westminster Abbey is the private crypt, and I had to pipe the ashes out and into the crypt. They need somebody who can do that without “excuse me, I need to just tune my pipes now, just hang on a minute”! You can’t do that. You’ve got to play, and you’ve got to get it right. It’s a very important function to play at. So the Duke needs not only someone who can actually perform, but somebody who can slot into those kind of situations.

“The only official function I have is the Shrove Tuesday football match. At a quarter past three I start playing in the courtyard of the castle and 1 pipe the football committee down to the green in front of the castle, the howff. It is basically a football match between the two Parish Councils of Alnwick. They knock merry hell out of each other on the excuse that they are kicking a football around the place. The first side to score two goals actually wins. But that is the only official function I have. When do you cease being the Duke’s Piper?

Well, when you start stealing like Jamie Allan, or insulting someone at the castle or maybe swearing at the Duke! Until I drop down dead, or I resign - then it is up to the Duke to ap- point somebody. I’m onto my third Duke now - at least it’s better than saying the Duke is onto his third Piper! I personally feel very privileged to have the position and very honoured to have it. As far as the piping fraternity is concerned, for some it is a much coveted job, for others there is a certain amount of ridicule for the post. But I personally think it should go on.”

A MUSICAL JOURNEY OF THE PIPES OF FRANCE

Jean Pierre Rasle followed the pattern on the day by interrupting his talk with illustrations of pipes and tunes. He delved as far back as the 12th century: “Historically we have got ref- erences of 12th century songs telling us about pipers and dancing and fairs and being at- tacked and having their bags pierced by jealous lovers!”

He talked of the ancient pipers only being allowed in the Churches at Christmas time if they

could play Christmas tunes.

He described how the development of French bagpipes followed two paths - those of the peasant and those of the gentry for whom the ancient makers were asked to refine the pipe and do away with the big drone. And from this was born the smallpipe, the musette, (often called the musette de cour), which flourished in the 17th and early 18th centuries. A book of the period said “Of all the musical instruments there is none so easy or handy than the smallpipe.”

Modifications included the replacement of the blow-pipe with the bellows - a necessary development as far as the nobility was con- cerned; it didn’t distort the features! And the well- known French woodwind maker Jaques Hotteterre (1674 - 1763), added a tiny extra chanter to increase their range upwards by 6

semi-tones. But by 1750 these pipes had died out completely in the face of competition from classical music imported from Italy and Germany. So by the end of the 18th century no-one was playing the baroque bagpipe (as it was sometimes called).

But the peasant bagpipe continued, although it was modified in the mid ninetenth century by Joseph Bechonet to give a combination of drones similar to the Musette.

“Although the Musette died out because of the influence of German and Italian classical music - it had a limited range and couldn’t modulate - some have suggested it died out be- cause all the players had their heads cut off during the French Revolution,” Jean-Pierre offered us with a twinkle!