Scottish Smallpipes and the Internet

Vicki Swan

For roughly 18 months now I have been researching teaching the Scottish smallpipes using the internet as a resource and tool. The folk music world has clashed on numerous occa sions with new fangled electrickery and many people resist getting hooked up to the net proclaiming it to be a waste of time, but could it be that the internet can help reach people who can’t get to sessions or a teacher? The following is a brief summary of the research that I’ve been performing. To see the research or even participating for the final disserta tion visit my masters website at: http://intra.ultralab.net/~vix/masters

Currently three pieces of research have been undertaken. These consist of teaching the Scottish Smallpipes using, i) a basic website, ii) webcasting and iii) podcasting. All three methods were successful at teaching tunes to pipers. Have a read and visit the websites, give the tunes a go yourself. All the materials are still there. If you fancy giving me some feed- back on what you think give me a shout! This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

i. Teaching the smallpipes using a basic website.

This study used various iterations of a tune learning website to evaluate what multimedia components most aided the learner in learning a tune online. A web site was created to teach folk tunes to Scottish Smallpipe players. Four scenarios of multimedia content were created in this website:

Audio

Audio and visual Audio, visual and text

Graphical and midi (computer generated audio)

Four different slow airs were selected for each scenario; tunes of the same type were chosen to remove the variable of tune difficulty from the equation. Thus the motivation for the learner was goal driven. Care was taken to make this a proximal goal (cf Hodges 2004).

Scenario 1: Audio

The teaching style for this tune was purely audio. The player clicked on the link and an mp3 was played. The tune was available in its entirety and also broken down into separate two bar phrases. This technique of learning by ear is a very common method of handing down music through generations of folk musicians, it is not so common amongst players who have gone through the much more formal and written “classical training”.

Scenario 2: Audio and Visual

This scenario was aimed at visual learners. As with the previous scenario, the learner clicked on the link, which this time brought up a small video close up on fingers of the tune

being played. As before the tune was available in its entirety and also broken down into separate two bar phrases. The theory behind this was to allow the visual learner to watch the fingering as the tune is being played.

Scenario 3: Audio, visual and text

The third style added written notation to both mp3s and movie clips. This combined both the previous styles of audio and visual, with written. Again the tune was played in full and broken down into two bar phrases.

Scenario 4: Graphical and midi (computer generated audio)

The fourth scenario was added to the web site to show a different use of technology. Using the music publishing program called Sibelius it is possible to publish tunes on a web site. This software gives playback using midi. It also provides the graphical notation and the ability to transpose the music into a different key (graphically and aurally)

Data Collection and Analysis

The initial response was good, many people expressed an interest in the web site. At this point, even before reaching any musical outcomes, two major difficulties were encountered with the technology;

The web site was created using an Apple Mac and the first problem encountered was for the people using PC’s. The movies and mp3s all needed to be played using a piece of software called Quicktime. Although links were given to be able to download this, it was a major stumbling block for many people.

Bandwidth was an issue for many people, although the files were compressed, they had to retain enough quality of sound and detail to be good enough to leam the tunes from. This meant that the files were still usually between 400kb and 2 Mb. Even with compression these files would take between 10 minutes and an hour to download.

To counter the problem of bandwidth the web site was transferred onto a CD ROM and posted out to people. This seemed like a good solution, but again, not everyone could get the disk to work. Although all the materials were provided on the disk, some computers in- sisted on trying to connect to the internet. It was found that users would give up relatively quickly if the site did not work readily. The added confusion and effort that the participant had to experience compromised the proximal event intended, (cf Hodges 2004).

For those participants that either did not experience access problems, or who managed to overcome them, the response was extremely favourable. Mr A was contacted through the Bellowspipes Newsgoup. He followed all the instructions on the web site and recorded all four of the tunes. Interestingly Mr A did not do all the tunes in order, but was very thorough in reading through the whole page before learning the tune. On occasion Mr A left the norm of textual e-mailing and corresponded in voice mail, this happened whenever he was re- cording a tune for the study. A possible reason for this departure from text could well be that he was responding to the stimulus from the web site, which was very much audio learning.

From learning all four tunes in this case the best method was to have the sheet music and the videos open; “I found myself finally having your video and the sheet music both open

on my laptop at the same time. This really works for me and is an incredibly rich way to learn.” (Mr A 2004)

Although Mr A liked to have the videos, Mr B (a piper who responded via an online blog) said; “I think the best system for myself as a lonely piper is the scorch system, in that one has the dots to help the initial memorising, the audio to key it in to the brain, and one can slow it right down if you want to. The videos are probably ok if you can project them but as has been said it's a bit difficult if yer optiks are not 20/20. The pure audio is ok for experi- enced and non music reading pipers but could cause one or two problems if you don’t have the same pitch pipes, mainly for the gracing and such.” (Mr B 2004 )

This was almost directly the opposite [to Mr A Ed], the part in common however being that the audio alone was not enough. Ms C (a piper contacted via Mudcat.org) however stated that; “I liked Scotty’s Last Munro the best. Although I didn’t use the videos much, I found it really useful to be able to listen to a phrase and then be able to read it at the same time. I did like the bit in Farewell to the Astra where there were two bars and then four bars and then the whole part ’ (Ms C 2004)

Already there is a pattern forming. The three players are all homing in on the audio aspect and the written notation aspect as being the salient parts to learning the tunes online. Matti Ruippo from the Sibelius Academy however states that; “It is not practical to build distance music studies upon a single method or medium. The teacher needs to support different learning styles and curves.” (Ruippo 2003:7)

The findings of this case study suggested that the participants coming from within online communities gave a more positive feedback of their experience and their learning outcomes than did the non-online community participants. This would suggest that some sort of basic community, (i.e. a forum for the learner to share and discuss their ideas with other people) may be beneficial or perhaps even requisite to the success of the learner.

The responses of the participants taken as a whole suggested that a variety of multimedia is required to cater for their varying learning styles. Finally an interesting finding was that the acoustic audio recording was seen as more valuable than the midi ii. representation avail- able in scenario 4.

ii Teaching the tunes using webcasts

The focus for this study was to pilot the concept of transferring the traditional music session, as seen predominantly in pubs, as a tune learning environment into an online environment.

In setting up an online session it was first important to break the concept into its constituent parts, both for the purpose of the study and for the purpose of the music. The following is a break down of the processes involved and some of the difficulties encountered.

- The music performance - the musicians

The remote musicians were drawn from a sample of musicians around the world. Adverts were placed in different places on the internet.

A group of colleagues were also enlisted to ensure a good rounded mix of performers. The final count for the last webcast included 2 performers in Canada, 3 in Holland and 1 in the north of England. In each case the performers had broadband internet access from home. The repertoire of tunes chosen for the webcast were in the main fairly well known to both performers and both had good computer literacy skills thus testing the concept and its po- tential as a learning environment.

- The Broadcast equipment and software

A digital video camera was procured from Ultralab. (An educational researcher facility with A.PU) Quicktime Broadcaster was available as a free downloaded from the apple website. A streaming server was already available for use at Ultralab. With only two people running the webcast it was difficult to facilitate both the cast, equipment, chat facility and maintain a constant stream of music. The webcasting took place from the front room of a residential property with broadband internet available.

- The Broadcast viewing software

The software required for viewing a webcast made by Quicktime Broadcaster is available as a free download from the internet. A website was created to show the participants how to log into the broadcast and also the chat facility. The major difficulty that was encountered was the software version. The version 6.3 was not sufficiently up to date for receiving the webcast. Participants had to upgrade to version 6.5. As the numbering between the two were so similar it some times took the participant some time to realise an upgrade was required.

- The social interaction - chat room

Several different options were explored for chat rooms. A chat room was not easily set up, so pre-existing ones were used. The first chat room (piperschat.com) worked well for the webcast team, but kept crashing in Holland. The second attempt was using MSN, however the servers were not functioning in Canada. A free chat room was set up hosted by a free service. This unfortunately had pop-ups (adverts opening up in different windows), but was reasonably stable and had the entire session team in.

- Feedback

The feedback was requested in the form of answers to a questionnaire, e-mail discussion and also at an internet forum set up for the purpose. The questions were fairly straightfor- ward. A transcript of the first chat session was kept, but unfortunately the chat crashed on the second webcast and only a few screen grabs were salvaged.

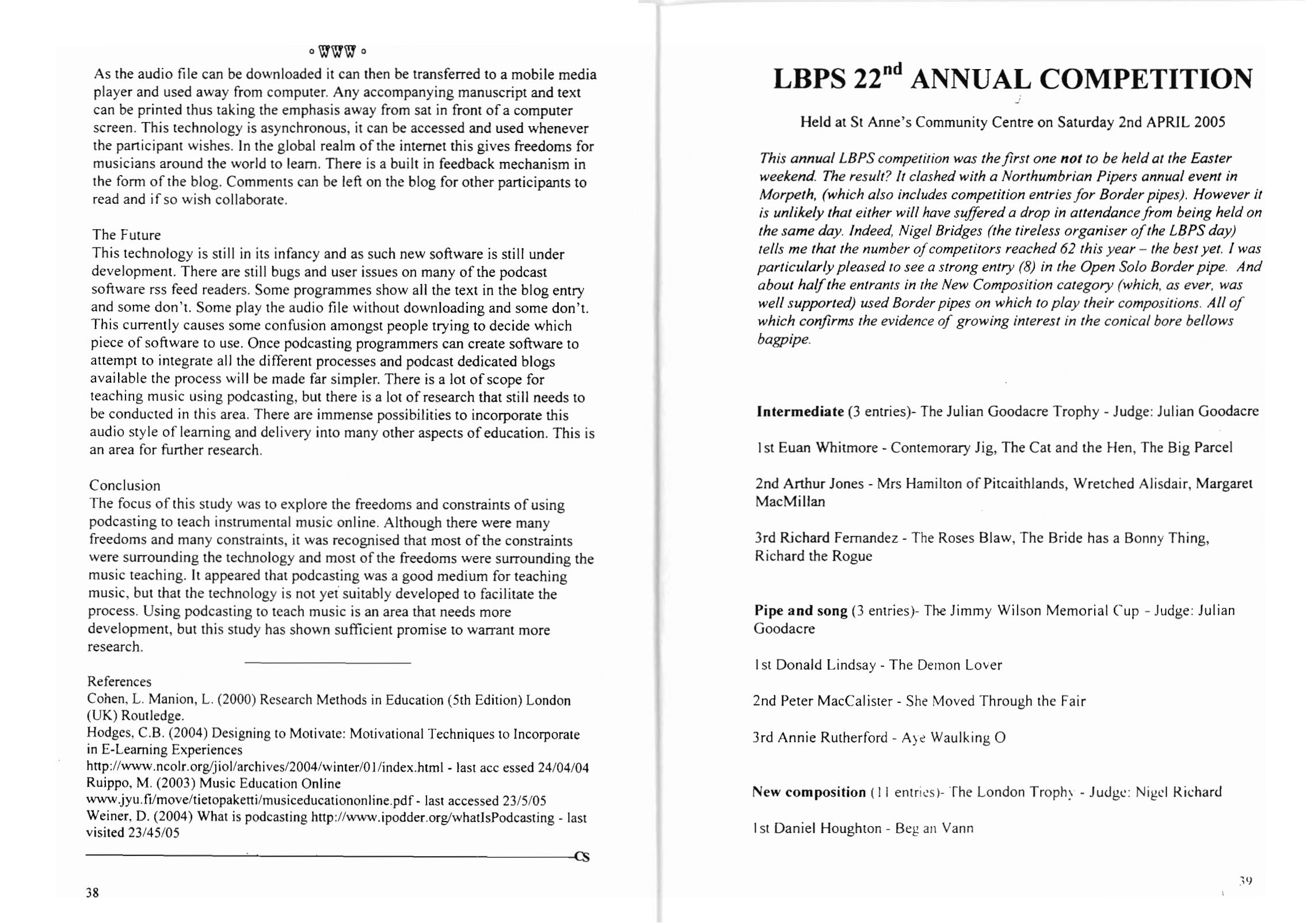

The areas of the webcast can be visually represented by the following diagram:-

Data Collection - The Webcasts

Two webcasts were held in November 2004 for the purposes of the pilot. This gave the opportunity to try out the technology and feedback mechanisms whilst using the action research spiral of planning, implementation, reflection, planning etc.

Webcast One - 7th November 2004

Prior to the webcast the equipment was set up and connected to the internet. There were two remote musicians (Scottish Smallpipers) taking part in webcast one, both domiciled in Holland. As they were both pipers it was decided on this occasion only to play pipe tunes.

As this cast was considered to be a technical test for the broadcast equipment the chat facil- ity had not been fully examined. The Dutch participants made their presence known through the message board; http://smallpiper.proboards38.com however it was quickly discovered that the message board was not synchronous enough to hold any kind of conversation. http://www.bagpipechat.com/ was chosen as the chat forum. This is a chat area for predomi- nantly highland pipers and was a quick and easy place to get to. Once the synchronous chat facility was in place all the participants were able to converse in real time. The full webcast took in the region of one hour. Feedback was requested in the form of both e-mails and on the message board, .com http://smallpiper.proboards38.com

Webcast Two - 14th November 2004

As a result of the feedback and reflection from the first webcast it was decided that the chat room needed more in-depth study and setting up before webcast number two. Several different free javascript chat sites were investigated and set up, but none were considered ideal. The MSN instant messenger was chosen to be the primary choice for the second web- cast and a free javascript room set up as a backup.

Also as a result of reflection and feedback post webcast one more tunes were uploaded to the information website. These tunes were far great in contrast and included both Scottish pipe tunes and non-Scottish pipes tunes. The webcast again was approximately one hour in duration and again feedback requested both in e-mails and in the forum. Although the web- cast team and the participants from Holland were able to log into MSN the Canadian and

English contingents failed to gain access to the chat area. As a result of this the fall back java chat room was used and all participants managed to communicate in this room.

Data analysis

Analysing the feedback the following trends can be seen:

- All participants played along, this was the aim of the study, so the webcast can be consid- ered

- New tunes were in general learnt, both by the playing along to the stream and from downloading the manuscript from the

- The participants didn’t in general have access to any other music session, that is they usually play either in a small group or alone and do not have access to music sessions in the pub setting to learn new

- The session was required to be live so that the participants felt part of a larger group and not just stuck at home playing by themselves. The video stream gave the participants a sense of audience, again, not feeling isolated. It also gave some of the visual cues that is in- tegral to performing music. The chat room was also necessary as this was the only medium for the participants to be able to give feedback. This moved the session from merely being a one way broadcast, much like the experience of watching television, to being an interactive

- The software was required to be totally up to If Quicktime 6.5 was not installed the broadcast could not be accessed.

Feedback from e-mails from the Dutch contingent brought up the question of the chat room further. It was suggested that a non java script chat room would be more efficient and also that the concept of having the video stream and the chat room integrated into the same browser window would be far easier for the participants to visually use.

Personal reflection on both the webcasts brought up the following observations:

- The chat room must be well established prior to the

- The chat room must be stable and easily

The first webcast used a message board as the communication area. The refresh time on this board was not sufficiently fast enough to enable real time chat so a backup room had to be found. On the second webcast the first choice of chat room was not reliable and so again a back up was used. As this was a pilot study the participants exhibited no outward frustration at this, but the webcast team found it a difficult to reconcile the attempts to appear as a pro- fessional musician whilst not having an immediately functioning chat facility.

- More than two people are required to take care of any technical

Being the webcast technician and major tune player it was very hard to cope with setting up the broadcast equipment, participate fully in the chat and troubleshoot any difficulties that were encountered. Trying to keep a continuous flow of audio / visual, keep the chat going and appear as a professional musician was not a feasible challenge.

- A small set list of tunes needs to be provided prior to the

Although a good size list of tunes available on the website ensures a good mix it is very hard for participants to choose, therefore a list of approximately 6 tunes needs to be listed at least a week in advance so that participants may, if they so wish prepare.

Conclusion

The aim of this pilot study was to test the functionality of the webcast equipment and the feedback systems. By performing two webcasts the equipment was tested, the chat feedback and questionnaire were piloted and feedback gained. The webcasts themselves were suc- cessful in that all the participants had an enjoyable experience and learned tunes they may not otherwise have done. As a result of the pilot the communication systems will be im- proved and a programme list of the tunes to be learnt for all the webcasts prepared in ad- vance.

This concept of learning via an online webcast is in itself cutting edge and the traditional folk scene will take some adjustment, but the benefits to the musicians that cannot access face to face tuition will soon dispel any scepticism.

iii Teaching the Smallpipes using podcasting

Podcasting is one of the latest technologies to emerge onto the computing scene and one that has a great deal to offer education. The purpose of this study was to use the action re- search methodology to investigate the freedoms and constraints of using podcasting to teach instrumental music online and gain an insight into whether it is a viable technology to pur- sue or just a fad.

Podcasting is so new that there is very little contemporaneous research, but is fast taking hold with more research papers becoming available everyday! To visit the podcast teaching site visit: http://smallpiper.blogspot.com/

Podcasting has taken its name from Apple’s iPod, but it is not a requirement to access this technology. Podcasting consists of several technologies all linked together to produce a new method of distribution. Dave Weiner (one of the founders of podcasting) describes podcast- ing like this: “Think how a desktop aggregator works. You subscribe to a set of feeds, and then can easily view the new stuff from all of the feeds together, or each feed separately.

Podcasting works the same way, with one exception. Instead of reading the new content on a computer screen, you listen to the new content on an iPod or iPod-like device.

Think of your iPod as having a set of subscriptions that are checked regularly for updates. Today there are a limited number of programs available this way. The format used is RSS

2.0 with enclosures.” (Weiner 2004)

Podcasts are generally between 10 minutes and and hour in length, the average being about 20 minutes and have a size of roughly 1Mb per minute of audio. As podcasting is still such a new technology the processes required to create and broadcast podcasts are still fairly complicated as there are no integrated programs or services as yet.

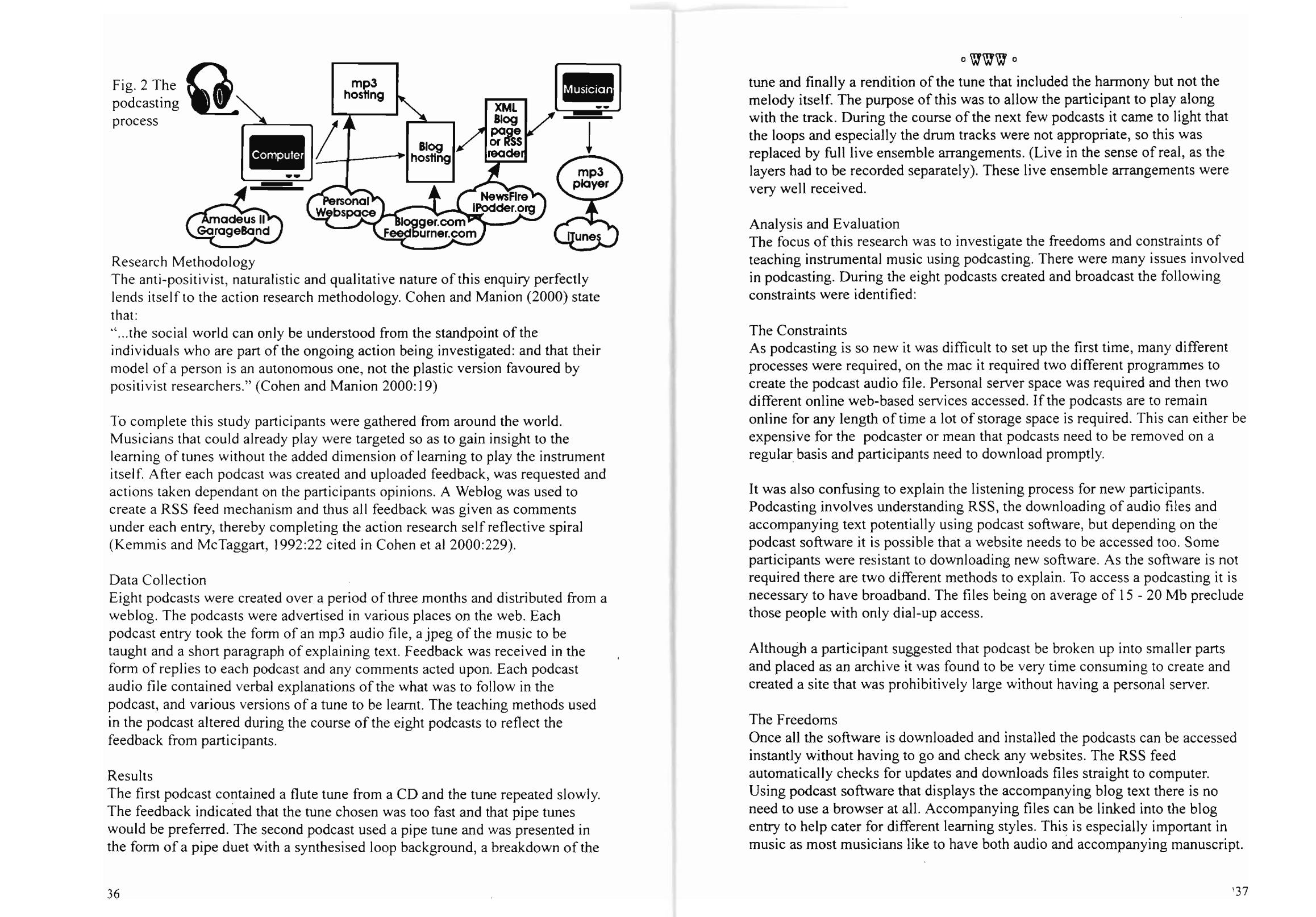

The following was the process used to create the podcasts for this study.

- A weblog was created using the free service com

- A com account was created.

- An audio file was recorded using the Apple Mac programmes GarageBand and Amadeus

- The file was saved as an mp3 and compressed a small

- The mp3 was uploaded into personal webspace. (Making a note of its address) A new en- try was created in the blog with the start of the entry being an a href html url link to the mp3 file, for example Error! Hyperlink reference not

The feed was ‘burned’ using feedburner.com to create an RSS that was podcast enabled. The RSS feed was advertised to find listeners.

Once a listener has discovered an RSS that they wish to subscribe to they need to add it to a feed aggregator. Once subscribed the feed will be checked at regular intervals by the aggre- gator and then new podcast entries can either be played or bounced into the relevant media player and from there straight into an iPod or other portable player for listening to at leisure.

The following is a representation of the process including suggested programmes (for the Mac OSX system)

Research Methodology

The anti-positivist, naturalistic and qualitative nature of this enquiry perfectly lends itself to the action research methodology. Cohen and Manion (2000) state that: “...the social world can only be understood from the standpoint of the individuals who are part of the ongoing action being investigated: and that their model of a person is an autonomous one, not the plastic version favoured by positivist researchers.” (Cohen and Manion 2000:19).

To complete this study participants were gathered from around the world. Musicians that could already play were targeted so as to gain insight to the learning of tunes without the added dimension of learning to play the instrument itself. After each podcast was created and uploaded feedback, was requested and actions taken dependant on the participants opin- ions. A Weblog was used to create a RSS feed mechanism and thus all feedback was given as comments under each entry, thereby completing the action research self reflective spiral (Kemmis and McTaggart, 1992:22 cited in Cohen et al 2000:229).

Data Collection

Eight podcasts were created over a period of three months and distributed from a weblog. The podcasts were advertised in various places on the web. Each podcast entry took the form of an mp3 audio file, a jpeg of the music to be taught and a short paragraph of explain- ing text. Feedback was received in the form of replies to each podcast and any comments acted upon. Each podcast audio file contained verbal explanations of the what was to follow in the podcast, and various versions of a tune to be leamt. The teaching methods used in the podcast altered during the course of the eight podcasts to reflect the feedback from partici- pants.

Results

The first podcast contained a flute tune from a CD and the tune repeated slowly. The feed- back indicated that the tune chosen was too fast and that pipe tunes would be preferred. The second podcast used a pipe tune and was presented in the form of a pipe duet with a synthe- sised loop background, a breakdown of the tune and finally a rendition of the tune that in- cluded the harmony but not the melody itself. The purpose of this was to allow the partici- pant to play along with the track. During the course of the next few podcasts it came to light that the loops and especially the drum tracks were not appropriate, so this was replaced by full live ensemble arrangements. (Live in the sense of real, as the layers had to be recorded separately). These live ensemble arrangements were very well received.

Analysis and Evaluation

The focus of this research was to investigate the freedoms and constraints of teaching in- strumental music using podcasting. There were many issues involved in podcasting. During the eight podcasts created and broadcast the following constraints were identified:

The Constraints

As podcasting is so new it was difficult to set up the first time, many different processes were required, on the mac it required two different programmes to create the podcast audio file. Personal server space was required and then two different online web-based services accessed. If the podcasts are to remain online for any length of time a lot of storage space is required. This can either be expensive for the podcaster or mean that podcasts need to be removed on a regular basis and participants need to download promptly.

It was also confusing to explain the listening process for new participants. Podcasting in- volves understanding RSS, the downloading of audio files and accompanying text poten- tially using podcast software, but depending on the podcast software it is possible that a website needs to be accessed too. Some participants were resistant to downloading new software. As the software is not required there are two different methods to explain. To ac- cess a podcasting it is necessary to have broadband. The files being on average of 15 - 20 Mb preclude those people with only dial-up access.

Although a participant suggested that podcast be broken up into smaller parts and placed as an archive it was found to be very time consuming to create and created a site that was

prohibitively large without having a personal server.

The Freedoms

Once all the software is downloaded and installed the podcasts can be accessed instantly without having to go and check any websites. The RSS feed automatically checks for updates and downloads files straight to computer. Using podcast software that displays the accompanying blog text there is no need to use a browser at all. Accompanying files can be linked into the blog entry to help cater for different learning styles. This is especially impor- tant in music as most musicians like to have both audio and accompanying manuscript.

As the audio file can be downloaded it can then be transferred to a mobile media player and used away from computer. Any accompanying manuscript and text can be printed thus tak- ing the emphasis away from sat in front of a computer screen. This technology is asynchro- nous, it can be accessed and used whenever the participant wishes. In the global realm of the internet this gives freedoms for musicians around the world to learn. There is a built in feedback mechanism in the form of the blog. Comments can be left on the blog for other participants to read and if so wish collaborate.

The Future

This technology is still in its infancy and as such new software is still under development. There are still bugs and user issues on many of the podcast software rss feed readers. Some programmes show all the text in the blog entry and some don’t. Some play the audio file without downloading and some don’t. This currently causes some confusion amongst people trying to decide which piece of software to use. Once podcasting programmers can create software to attempt to integrate all the different processes and podcast dedicated blogs available the process will be made far simpler. There is a lot of scope for teaching music using podcasting, but there is a lot of research that still needs to be conducted in this area. There are immense possibilities to incorporate this audio style of learning and delivery into many other aspects of education. This is an area for further research.

Conclusion

The focus of this study was to explore the freedoms and constraints of using podcasting to teach instrumental music online. Although there were many freedoms and many constraints, it was recognised that most of the constraints were surrounding the technology and most of the freedoms were surrounding the music teaching. It appeared that podcasting was a good medium for teaching music, but that the technology is not yet suitably developed to facili- tate the process. Using podcasting to teach music is an area that needs more development, but this study has shown sufficient promise to warrant more research.

References

Cohen, L. Manion, L. (2000) Research Methods in Education (5th Edition) London (UK) Routledge.

Hodges, C.B. (2004) Designing to Motivate: Motivational Techniques to Incorporate in E-Leaming Experiences http://www.ncolr.org/jiol/archives/2004/winter/01/index.html - last acc essed 24/04/04 Ruippo, M. (2003) Music Education Online

www.jyu.fi/move/tietopaketti/musiceducationonline.pdf - last accessed 23/5/05

Weiner, D. (2004) What is podcasting http://www.ipodder.org/whatIsPodcasting - last visited 23/45/05