From Harvest to Market - Piping in Cambeltown at Harvest and Fair

From harvest to market

Keith Sanger looks at the former role of the piper in rural society, and warns against making too many assumptions.

WHILE there is a tendency to compartmentalise piping into neat boxes with Highland/ military in one and Lowland/town pipers in the other, there was actually a large and common middle ground shared by nearly all pipers. Professional specialisation is a relatively modern concept and up to the 18th century, even in Scotland's largest towns, most people had one foot in the countryside, which would have been only walking distance away.

Food consumed a very large portion of relative income and the success or otherwise of the harvest had an immediate effect at all levels. Even at the very top of the piping tree, where the piper held land in exchange for his piping duties, it was primarily the raising and selling of his “beastes” or cattle that actually produced the income.(1)

When it came to harvest it tended to be a case of all available hands, and even as late as the Napoleonic wars there is evidence, usually from contemporary newspaper reports that the various fencible regiments, who were mostly quartered on the local populations, voluntarily pitched in to help at harvest time. In one instance the correspondence of the Breadalbane Fencibles shows that even the 13 musicians of the regimental band were offered as reapers. In this case the help was as labour, but harvesting was hard work and the

use of a local piper to give encouragement goes back probably as far as the point that the instrument became loud enough to carry to a band of open air workers. It was certainly an established practice by 1574, when a payment “To ane pyper to play to the scheraris in harvest, £4” was recorded in the accounts of Douglas of Lochleven in Fife.(2)

Exactly how widespread the practice was and when it was discontinued is a more difficult question to answer from the limited recorded payments so far identified. Certainly on the large North-East estate of

the Duke of Gordon, a piper called William Robertson in Fochaber was paid ten merks of Scots money in 1715 for “attending to the people at come and hay” and in 1770 one Peter Munro Piper received payment of one pound sterling at Gordon Castle for “playing to the Hay makers & the Shearers in harvest”.(3) In all of these instances it is, of course, an assumption that the pipers were being paid to play while the work

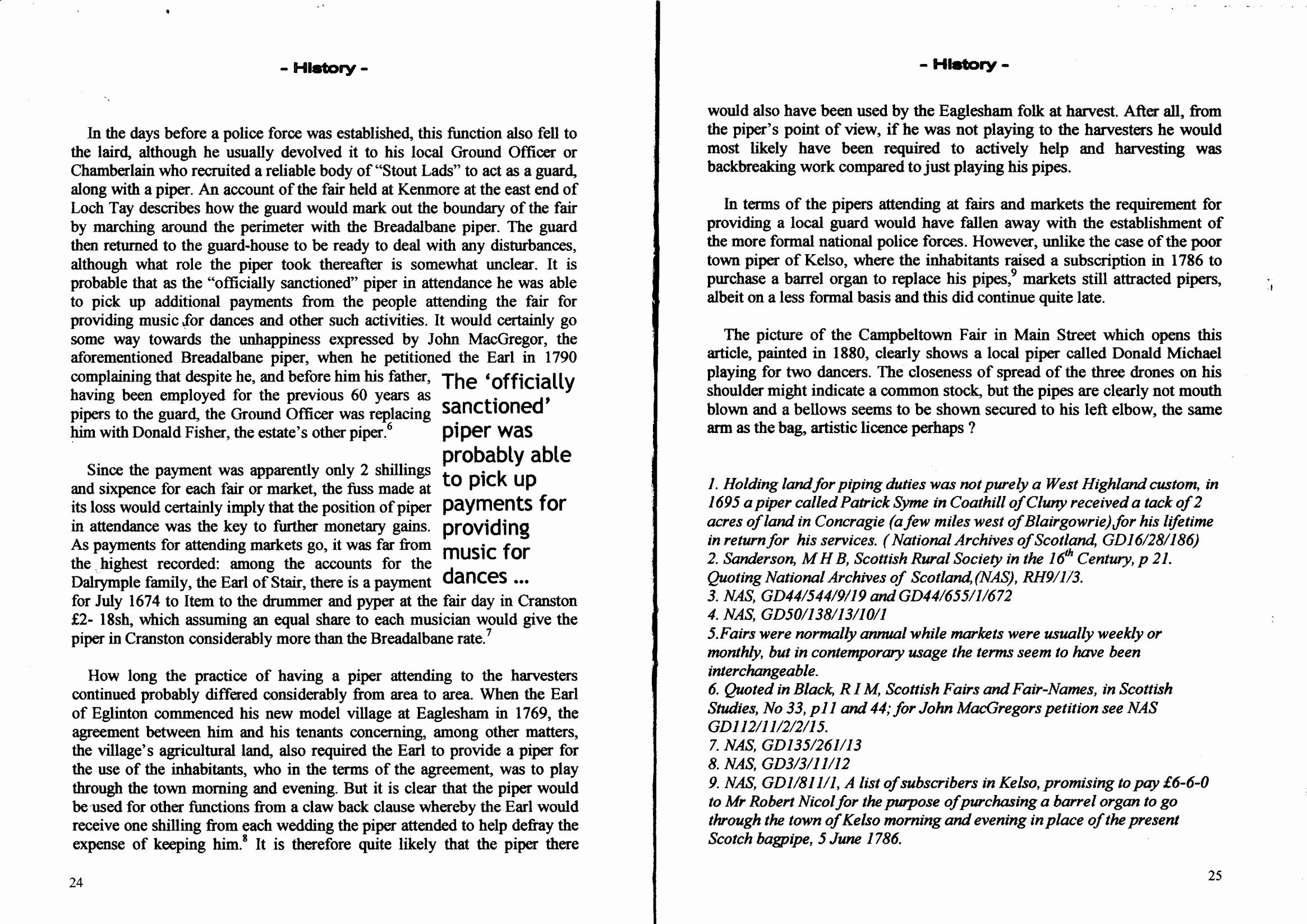

Campbeltown Fair detail, showing piper Donald Michael and left-hand bellows - artistic licence?

was in progress rather than providing the music for dancing after the work was over.

Following a harvest, even on a “self- sufficient” smallholding, a portion of the produce would still need to be sold to meet any extra levies which were due. For example, church dues, or a portion of the schoolmasters salary and, in one case of a piper in Perthshire, what was described as 1/3 of a Crew wedder rendered at 11 shillings and 8 pence in money which turned out to be his portion of supplying a sheep as victuals to the crew of the local boat.(4)

For those close to a town, access to a market was easy and frequent, but for most of rural Scotland it was a case of the market had to come to the seller and there had grown up a regular system of fairs and markets.(5) These were usually held under the authority of the local laird and, as they involved large gatherings of people, required policing.

In the days before a police force was established, this function also fell to the laird, although he usually devolved it to his local Ground Officer or Chamberlain who recruited a reliable body of “Stout Lads” to act as a guard, along with a piper. An account of the fair held at Kenmore at the east end of Loch Tay describes how the guard would mark out the boundary of the fair by marching around the perimeter with the Breadalbane piper. The guard then returned to the guard-house to be ready to deal with any disturbances, although what role the piper took thereafter is somewhat unclear. It is probable that as the “officially sanctioned” piper in attendance he was able to pick up additional payments from the people attending the fair for providing music for dances and other such activities. It would certainly go some way towards the unhappiness expressed by John MacGregor, the aforementioned Breadalbane piper, when he petitioned the Earl in 1790 complaining that despite he, and

before him his father, having been employed for the previous 60 years as pipers to the guard, the Ground Officer was replacing him with Donald Fisher, the estate's other piper.(6)

Since the payment was apparently only 2 shillings and sixpence for each fair or market, the fuss made at its loss would certainly imply that the position of piper in attendance was the key to further monetary gains. As payments for attending markets go, it was far from the highest recorded: among the accounts for the Dalrymple family, the Earl of Stair, there is a payment for July 1674 to Item to the drummer and pyper at the fair day in Cranston £2- 18sh, which assuming an equal share to each musician would give the piper in Cranston considerably more than the Breadalbane rate.(7)

How long the practice of having a piper attending to the harvesters continued probably differed considerably from area to area. When the Earl of Eglinton commenced his new model village at Eaglesham in 1769, the agreement between him and his tenants concerning, among other matters, the village's agricultural land, also required the Earl to provide a piper for the use of the inhabitants, who in the terms of the agreement, was to play through the town morning and evening. But it is clear that the piper would be used for other functions from a claw back clause whereby the Earl would receive one shilling from each wedding the piper attended to help defray the expense of keeping him.(8) It is therefore quite likely that the piper there would also have been used by the Eaglesham folk at harvest. After all, from the piper's point of view, if he was not playing to the harvesters he would most likely have been required to actively help and harvesting was backbreaking work compared to just playing his pipes.

In terms of the pipers attending at fairs and markets the requirement for providing a local guard would have fallen away with the establishment of the more formal national police forces. However, unlike the case of the poor town piper of Kelso, where the inhabitants raised a subscription in 1786 to purchase a barrel organ to replace his pipes,(9) markets still attracted pipers, albeit on a less formal basis and this did continue quite late.

The picture of the Campbeltown Fair in Main Street which opens this article, painted in 1880, clearly shows a local piper called Donald Michael playing for two dancers. The closeness of spread of the three drones on his shoulder might indicate a common stock, but the pipes are clearly not mouth blown and a bellows seems to be shown secured to his left elbow, the same arm as the bag, artistic licence perhaps?

- Holding land for piping duties was not purely a West Highland custom, in 1695 a piper called Patrick Syme in Coathill of Cluny received a tack of 2 acres of land in Concragie (a few miles west of Blairgowrie) for his lifetime in return for his services. ( National Archives of Scotland, GDI6/28/186)

- Sanderson, MH B, Scottish Rural Society in the 16,h Century, p 21. Quoting National Archives of Scotland, (NAS), RH9/1/3. (3)NAS, GD44/544/9/19 andGD44/655/l/672

(4)NAS, GD50/138/13/10/1

- Fairs were normally annual while markets were usually weekly or monthly, but in contemporary usage the terms seem to have been

- Quoted in Black, RIM, Scottish Fairs and Fair-Names, in Scottish Studies, No 33, pll and 44; for John MacGregors petition see NAS GDI 12/11/2/2/15.

(7)NAS, GD135/261/13 (8)NAS, GD3/3/11/12

(9)NAS, GD1/811/1, A list of subscribers in Kelso, promising to pay £6-6-0 to Mr Robert Nicol for the purpose of purchasing a barrel organ to go through the town of Kelso morning and evening in place of the present Scotch bagpipe, 5 June 1786