Seeking the Lowland Bagpipe

Seeking the Lowland bagpipe

Pete Stewart recounts how the writing of his second book on Lowland piping, Welcome Home My Dearie, took a rather unexpected turn at the eleventh hour.

IT'S MID-OCTOBER, 2008, and I have a deadline. In order to launch my new book at the Lowland and Border Pipers' Society Annual Collogue on November 15th. I must finish the final draft of the text by tomorrow. I have one final image to describe, one which I have decided to include in an appendix, since, while fascinating, it seems somewhat peripheral to my argument. It appears to have come from America in the years immediately before the Declaration of Independence, or so I have deduced from the information I have gleaned from the wonderful website of Aron Garceau (www.prydein.com/pipes).

Transatlantic sessions? The Music Club, published, seemingly in America, in 1772

It is an engraving entitled The Music Club, published by one Robert Sayer, who published many satirical cartoons in the 1770s concerning the state of the American colonies, as well as some of the earliest maps of the “New World”. However, there is, I now note, another name visible on the print, that of Hemskirk. I know nothing of this name, but a quick internet search informs me that Egbert van Heemskerk (as the Dutch spelling has it) is the name of at least two, possibly three generations of Dutch painters, the middle one of which lived in England from 1674 onwards, being followed in his trade by his son of the same name, who died in 1744. There also appears to be an earlier generation, dying in Holland in 1680, though Wikipedia denies his existence.

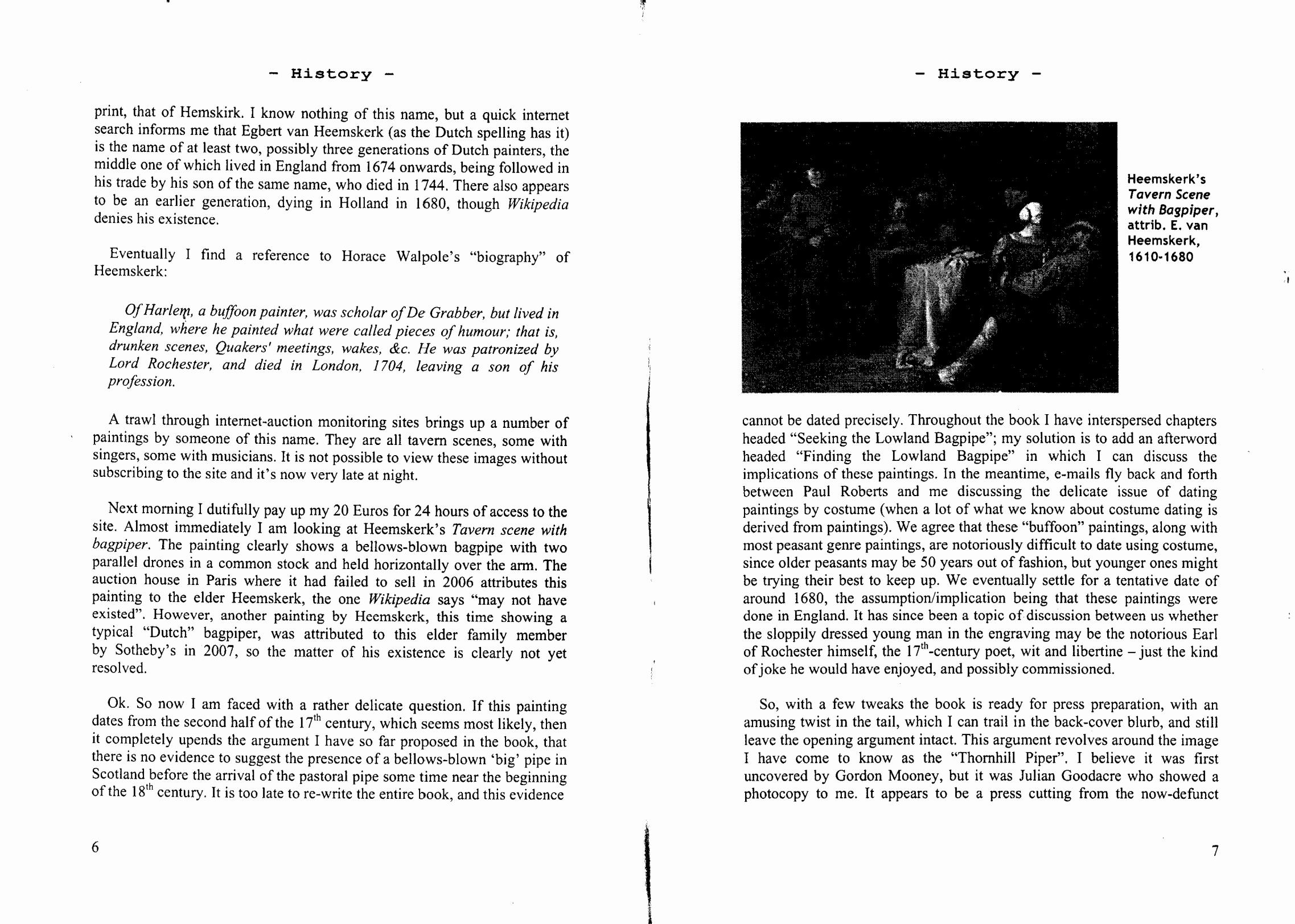

Heemskerk’s Tavern Scene with Bagpiper, (detail) attrib. E. van Heemskerk, 1610- 1680

Eventually I find a reference to Horace Walpole's “biography” of Heemskerk:

0ƒ Harlem, a buƒƒoon painter, was scholar oƒ De Grabber, but lived in England, where he painted what were called pieces oƒ humour; that is, drunken scenes, Quakers' meetings, wakes, &c. He was patronized by Lord Rochester, and died in London, 1704, leaving a son oƒ his proƒession.

A trawl through internet-auction monitoring sites brings up a number of paintings by someone of this name. They are all tavern scenes, some with singers, some with musicians. It is not possible to view these images without subscribing to the site and it's now very late at night.

Next morning I dutifully pay up my 20 Euros for 24 hours of access to the site. Almost immediately I am looking at Heemskerk's Tavern scene with bagpiper. The painting clearly shows a bellows-blown bagpipe with two parallel drones in a common stock and held horizontally over the arm. The auction house in Paris where it had failed to sell in 2006 attributes this painting to the elder Heemskerk, the one Wikipedia says “may not have existed”. However, another painting by Heemskerk, this time showing a typical “Dutch” bagpiper, was attributed to this elder family member by Sotheby's in 2007, so the matter of his existence is clearly not yet resolved

Ok. So now I am faced with a rather delicate question. If this painting dates from the second half of the 17th century, which seems most likely, then it completely upends the argument I have so far proposed in the book, that there is no evidence to suggest the presence of a bellows-blown ‘big' pipe in Scotland before the arrival of the pastoral pipe some time near the beginning of the 18th century. It is too late to re-write the entire book, and this evidence cannot be dated precisely. Throughout the book I have interspersed chapters headed “Seeking the Lowland Bagpipe”; my solution is to add an afterword headed “Finding the Lowland Bagpipe” in which I can discuss the implications of these paintings. In the meantime, e-mails fly back and forth between Paul Roberts and me discussing the delicate issue of dating paintings by costume (when a lot of what we know about costume dating is derived from paintings). We agree that these “buffoon” paintings, along with most peasant genre paintings, are notoriously difficult to date using costume, since older peasants may be 50 years out of fashion, but younger ones might be trying their best to keep up.

We eventually settle for a tentative date of around 1680, the assumption/implication being that these paintings were done in England. It has since been a topic of discussion between us whether the sloppily dressed young man in the engraving may be the notorious Earl of Rochester himself, the 17th-century poet, wit and libertine - just the kind of joke he would have enjoyed, and possibly commissioned.

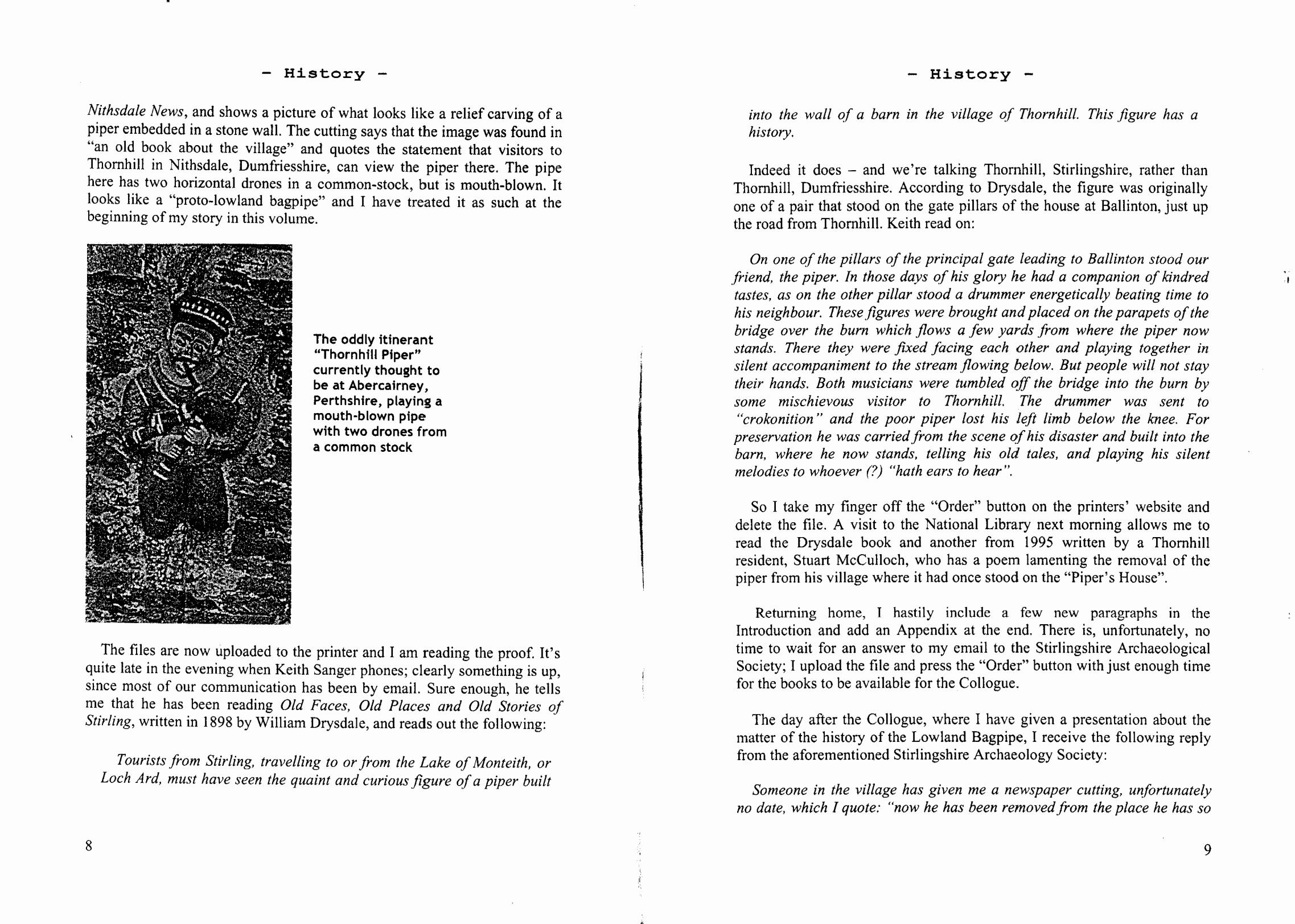

So, with a few tweaks the book is ready for press preparation, with an amusing twist in the tail, which I can trail in the back-cover blurb, and still leave the opening argument intact. This argument revolves around the image I have come to know as the “ThornhillPiper”. I believe it was first uncovered by Gordon Mooney, but it was Julian Goodacre who showed a photocopy to me. It appears to be a press cutting from the now-defunct Nithsdale News, and shows a picture of what looks like a relief carving of a piper embedded in a stone wall. The cutting says that the image was found in “an old book about the village” and quotes the statement that visitors to Thornhill in Nithsdale, Dumfriesshire, can view the piper there.

The pipe here has two horizontal drones in a common-stock, but is mouth-blown. It looks like a “proto-lowland bagpipe” and I have treated it as such at the beginning of my story in this volume.

(left) The oddly itinerant “Thornhill Piper” currently thought to be at Abercairney, Perthshire, playing a mouth-blown pipe with two drones from a common stock

The files are now uploaded to the printer and I am reading the proof. It's quite late in the evening when Keith Sanger phones; clearly something is up, since most of our communication has been by email

Sure enough, he tells me that he has been reading 0ld Faces, 0ld Places and 0ld Stories oƒ Stirling, written in 1898 by William Drysdale, and reads out the following:

Tourists ƒrom Stirling, travelling to or ƒrom the Lake oƒ Monteith, or Loch Ard, must have seen the quaint and curious ƒigure oƒ a piper built into the wall oƒ a barn in the village oƒ Thornhill. This ƒigure has a history.

Indeed it does - and we're talking Thornhill, Stirlingshire, rather than Thornhill, Dumfriesshire. According to Drysdale, the figure was originally one of a pair that stood on the gate pillars of the house at Ballinton, just up the road from Thornhill. Keith read on:

0n one oƒ the pillars oƒ the principal gate leading to Ballinton stood our ƒriend, the piper. In those days oƒ his glory he had a companion oƒ kindred tastes, as on the other pillar stood a drummer energetically beating time to his neighbour. These ƒigures were brought and placed on the parapets oƒ the bridge over the burn which ƒlows a ƒew yards ƒrom where the piper now stands. There they were ƒixed ƒacing each other and playing together in silent accompaniment to the stream ƒlowing below. But people will not stay their hands. Both musicians were tumbled oƒƒ the bridge into the burn by some mischievous visitor to Thornhill. The drummer was sent to “crokonition” and the poor piper lost his leƒt limb below the knee. For preservation he was carried ƒrom the scene oƒ his disaster and built into the barn, where he now stands, telling his old tales, and playing his silent melodies to whoever (?) “hath ears to hear”.

So I take my finger off the “Order” button on the printers' website and delete the file. A visit to the National Library next morning allows me to read the Drysdale book and another from 1995 written by a Thornhill resident, Stuart McCulloch, who has a poem lamenting the removal of the piper from his village where it had once stood on the “Piper's House”.

Returning home, I hastily include a few new paragraphs in the Introduction and add an Appendix at the end. There is, unfortunately, no time to wait for an answer to my email to the Stirlingshire Archaeological Society; I upload the file and press the “Order” button with just enough time for the books to be available for the Collogue.

The day after the Collogue, where I have given a presentation about the matter of the history of the Lowland Bagpipe, I receive the following reply from the aforementioned Stirlingshire Archaeology Society:

Someone in the village has given me a newspaper cutting, unƒortunately no date, which I quote: “now he has been removed ƒrom the place he has so long occupied by the ƒactor to Captain Drummond Moray oƒ Abercairney, Crieƒƒ and the conjecture is that he will be ƒound there in the ƒuture. But whatever his ultimate destination may be, Thornhill is sorry at losing its old piper and his removal has called ƒorth the ƒollowing lines ƒrom a correspondent”.

The cutting is very ƒragile and I have not included the short poem as it is not easy to decipher. I hope that this will be some help. (1)

On Tuesday, I visit the library of the Royal Commission for Ancient and Historical Monuments in Scotland

I explain my mission and am presented with a box-file of pictures of the so-called Abercairney Abbey in Perthshire, which was demolished in 1960. I begin to look through a large pile of mounted photos of exteriors and interiors of the house and a lot of aerial photos of the estate. I am about to abandon the search but decide to simply rifle through the pile; the first thing I find is the picture on the cover of this issue. The photo is dated 1923 and a hand-written caption says “Fowlis piper built into stable wall”. Whoops of delight are, I'm glad to say, apparently perfectly acceptable in this most un-intimidating of libraries.

Sometime between 1898 and 1923, the carving was removed from the Thornhill barn, and its layer of paint has subsequently eroded away (unless it was cleaned when moved). But it is clearly the same piper, though he has lost his blowpipe; or was it painted on in the first place? There appears to be the remains of a stock in the Abercairny picture, but unless the stable block survived demolition it may be impossible to tell for certain. A visit is planned.

Two questions remain. Firstly, why did Capt. Drummond Murray go to the trouble of taking this carving out of the wall in Thornhill and moving it to fill a hole in his stable wall? Secondly, what is the relationship between this carving and the eerily similar one, reproduced on the cover of the June 2008 issue of this journal, now at Skirling in Peebleshire, which in the previous issue of Common Stock I suggested was possibly the oldest piper in Scotland? Do I have to revise that opinion as well? One thing is for sure, you never know what's lurking round the next shelf in the piping archive …

- After I'd written this article, the press-cutting arrived; along with the poem it includes a drawing of the piper; both were printed by McCulloch, and reproduced in ‘Welcome Home My Dearie'. I have not yet located the origin of this cutting, but clearly it must predate

The once-flourishing weaving village of Fowlis Wester lies to the west of Abercairney estate.