The Piper Has Gone for a Soldier

>

Keith Sanger delves into the muster rolls for records of Lowland players in some of the early pipe bands

A SCOTTISH regiment with pipe band, usually with its pipers kilted and tartan clad, has become the standard military concept of Scotland, but behind that image lies a far more complex picture in terms of how pipes and the military evolved. Pipe bands as such were certainly a late and peculiarly military invention which appeared during the early decades of the 19th century and were closely linked to the role of the Highland piper and his “Highland or Military Bagpipes”, as just about all the pipemakers' catalogues tended to describe them until recently However, any idea that what happened in the 19th century can be taken as a guide to earlier periods does not fit with the albeit limited evidence that does exist.

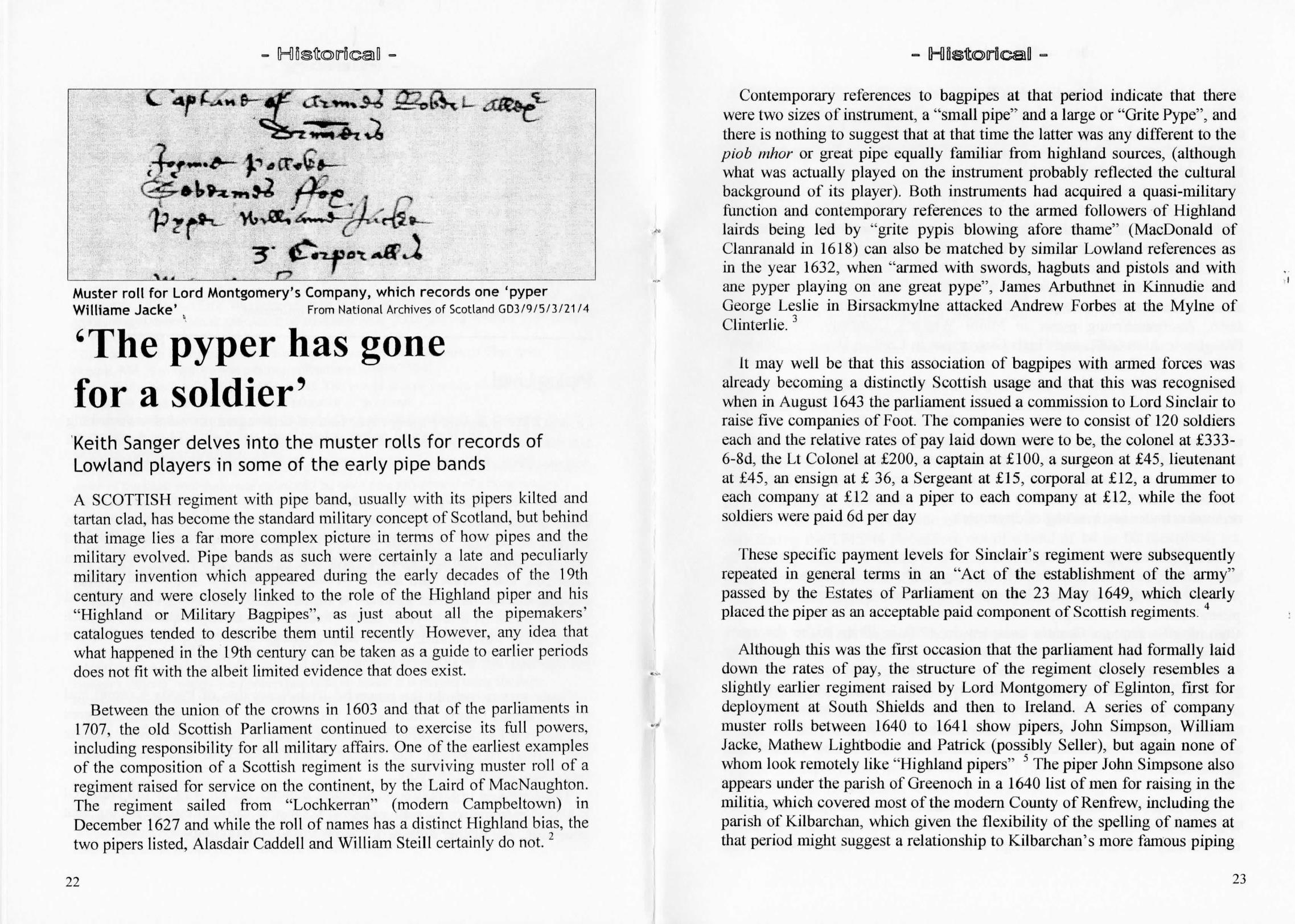

Between the union of the crowns in 1603 and that of the parliaments in 1707, the old Scottish Parliament continued to exercise its full powers, including responsibility for all military affairs. One of the earliest examples of the composition of a Scottish regiment is the surviving muster roll of a regiment raised for service on the continent, by the Laird of MacNaughton. The regiment sailed from “Lochkerran” (modern Campbeltown) in December 1627 and while the roll of names has a distinct Highland bias, the two pipers listed, Alasdair Caddell and William Steill certainly do not.(2)

Contemporary references to bagpipes at that period indicate that there were two sizes of instrument, a “small pipe” and a large or “Grite Pype”, and there is nothing to suggest that at that time the latter was any different to the piob mhor or great pipe equally familiar from

highland sources, (although what was actually played on the instrument probably reflected the cultural background of its player). Both instruments had acquired a quasi-military function and contemporary references to the armed followers of Highland lairds being led by “grite pypis blowing afore thame” (MacDonald of Clanranald in 1618) can also be matched by similar Lowland references as in the year 1632, when “armed with swords, hagbuts and pistols and with ane pyper playing on ane great pype”, James Arbuthnet in Kinnudie and George Leslie in Birsackmylne attacked Andrew Forbes at the Mylne of Clinterlie.(3)

It may well be that this association of bagpipes with armed forces was already becoming a distinctly Scottish usage and that this was recognised when in August 1643 the parliament issued a commission to Lord Sinclair to raise five companies of Foot. The companies were to consist of 120 soldiers each and the relative rates of pay laid down were to be, the colonel at £333- 6-8d, the Lt Colonel at £200, a captain at £100, a surgeon at £45, lieutenant at £45, an ensign at £ 36, a Sergeant at £15, corporal at £12, a drummer to each company at £12 and a piper to each company at £12, while the foot soldiers were paid 6d per day.

These specific payment levels for Sinclair's regiment were subsequently repeated in general terms in an “Act of the establishment of the army” passed by the Estates of Parliament on the 23 May 1649, which clearly placed the piper as an acceptable paid component of Scottish regiments.(4)

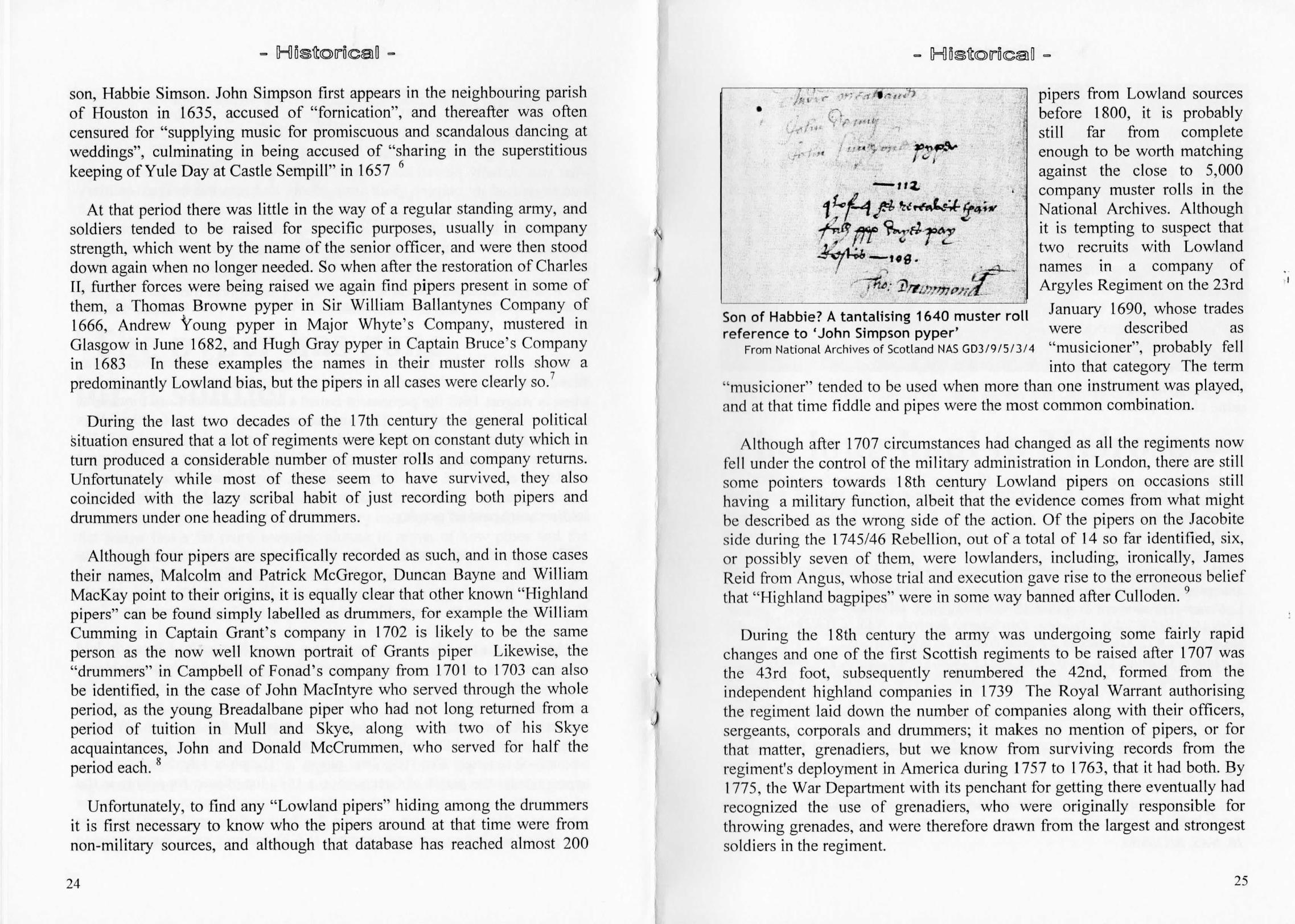

Although this was the first occasion that the parliament had formally laid down the rates of pay, the structure of the regiment closely resembles a slightly earlier regiment raised by Lord Montgomery of Eglinton, first for deployment at South Shields and then to Ireland. A series of company muster rolls between 1640 to 1641 show pipers, John Simpson, William Jacke, Mathew Lightbodie and Patrick (possibly Seller), but again none of whom look remotely like “Highland pipers”.(5) The piper John Simpsone also appears under the parish of Greenoch in a 1640 list of men for raising in the militia, which covered most of the modem County of Renfrew, including the parish of Kilbarchan, which given the flexibility of the spelling of names at that period might suggest a relationship to Kilbarchan's more famous piping son, Habbie Simson. John Simpson first appears in the neighbouring parish of Houston in 1635, accused of “fornication”, and thereafter was often censured for “supplying music for promiscuous and scandalous dancing at weddings”, culminating in being accused of “sharing in the superstitious keeping of Yule Day at Castle Sempill” in 1657. (6)

At that period there was little in the way of a regular standing army, and soldiers tended to be raised for specific purposes, usually in company strength, which went by the name of the senior officer, and were then stood down again when no longer needed. So when after the restoration of Charles II, further forces were being raised we again find pipers present in some of them, a Thomas Browne pyper in Sir William Ballantynes Company of 1666, Andrew Young pyper in Major Whyte's Company, mustered in Glasgow in June 1682, and Hugh Gray pyper in Captain Bruce's Company in 1683 In these examples the names in their muster rolls show a predominantly Lowland bias, but the pipers in all cases were clearly so.(7)

During the last two decades of the 17th century the general political situation ensured that a lot of regiments were kept on constant duty which in turn produced a considerable number of muster rolls and company returns. Unfortunately while most of these seem to have survived, they also coincided with the lazy scribal habit of just recording both pipers and drummers under one heading of drummers.

Although four pipers are specifically recorded as such, and in those cases their names, Malcolm and Patrick McGregor, Duncan Bayne and William MacKay point to their origins, it is equally clear that other known “Highland pipers” can be found simply labelled as drummers, for example the William Cumming in Captain Grant's company in 1702 is likely to be the same person as the now well known portrait of Grant's piper. Likewise, the “drummers” in Campbell of Fonad's company from 1701 to 1703 can also be identified, in the case of John MacIntyre who served through the whole period, as the young Breadalbane piper who had not long returned from a period of tuition in Mull and Skye, along with two of his Skye acquaintances, John and Donald McCrummen, who served for half the period each.(8)

Unfortunately, to find any “Lowland pipers” hiding among the drummers it is first necessary to know who the pipers around at that time were from non-military sources, and although that database has reached almost 200 pipers from Lowland sources before 1800, it is probably still far from complete enough to be worth matching against the close to 5,000 company muster rolls in the National Archives. Although it is tempting to suspect that two recruits with Lowland names in a company of Argyles Regiment on the 23rd January 1690, whose trades were described as “musicioner”, probably fell into that category. The term “musicioner” tended to be used when more than one instrument was played, and at that time fiddle and pipes were the most common combination.

Although after 1707 circumstances had changed as all the regiments now fell under the control of the military administration in London, there are still some pointers towards 18th century Lowland pipers on occasions still having a military function, albeit that the evidence comes from what might be described as the wrong side of the action. Of the pipers on the Jacobite side during the 1745/46 Rebellion, out of a total of 14 so far identified, six, or possibly seven of them, were lowlanders, including, ironically, James Reid from Angus, whose trial and execution gave rise to the erroneous belief that “Highland bagpipes” were in some way banned after Culloden.(9)

During the 18th century the army was undergoing some fairly rapid changes and one of the first Scottish regiments to be raised after 1707 was the 43rd foot, subsequently renumbered the 42nd, formed from the independent highland companies in 1739. The Royal Warrant authorising the regiment laid down the number of companies along with their officers, sergeants, corporals and drummers; it makes no mention of pipers, or for that matter, grenadiers, but we know from surviving records from the regiment's deployment in America during 1757 to 1763, that it had both. By 1775, the War Department with its penchant for getting there eventually had recognized the use of grenadiers, who were originally responsible for throwing grenades, and were therefore drawn from the largest and strongest soldiers in the regiment.

By that date the grenadiers had become the “show company” and thereafter all the Warrants issued to raise new regiments in the UK specified that there should be a Grenadier company which, apart from the usual two drummers per company would in addition have two fifers. In the warrants issued for raising Highland regiments after 1775, Grenadier companies were given two pipers instead of fifers and as most of the new Scottish regiments raised after that date were Highland, this appears to have set a pattern.

However, having an establishment of two pipers and actually finding Highland pipers to fill it were two different matters and the contemporary evidence shows that Highland pipers were in short supply For example, the two pipers in the second battalion of the 71st Highlanders on route to North America in 1776 were a James Munro, a native of Caithness who after his return to Scotland in 1785 became a bagpipe maker and piper to the Canongate in Edinburgh, and the other was an Archibald Baxter whose name clearly points to a Lowland origin. (10)

References

- With apologies to the American Civil War song ‘Johnny's gone for a soldier'

- Highland Papers, vol I, edited for the Scottish History Society by J R N MacPhail, (1914). pp 114-115.

- The Register of the Privy Council of Scotland, volume XI, p 463-464, Second Series volume IV p 434

- The Records of the Parliaments of Scotland to 1707 M. Brown et al eds, (St Andrews, 2007), online version at www.rps.ac.uk. 1643/6/85 and 1649/5/165.

- National Archives of Scotland, (NAS), GD3/9/5/4, GD3/9/5/3/21

- NAS GD3/9/5/3/9, Paisley Presbytery Records NAS CH2/294/2/87 and MacKenzie, R D, Kilbarchan a Parish History, (1902), p 67 77

- Dalton, Charles, The Scots Army 1661 1688, (1909), pp 78, 128 and

8. NAS, E100/14/13, E100/38/2, E100/38/4, E100/38/6, E100/38/6, E100/38/7 and El00/38/11

9. The pipers were John Ballantine, Nicholas Carr Robert Jamieson, James Reid, John Sinclair and William Webster The possible seventh was Donald Ferguson of Colonel John Stewart's Regiment predominantly raised in and known as the Edinburgh Regiment. Gordon, Sir Bruce Seton and Arnot, J G, ‘The Prisoners of the ‘45, edited from the State papers' (Scottish History Society, 1929) and Livingstone, A, Aikman, C W H and Hart, B, 'Muster Roll of Prince Charles Edwards Army, 1745 46, (1984).

10. NAS, RH2/8/80