The Rosetta Stone Of Scottish Piping

WITH SO much known and written about the Northumbrian smallpipes, it may perhaps seem difficult or unnecessary to construct a distinct case history for the Scottish smallpipes. When these instruments thrived in a larger culture province than today, categorical distinctions would not have been drawn as they now are; the same general type of smallpipe or chamber bagpipe was played on both sides of the Border and indeed all over Scotland and at least in the north of England and perhaps beyond.

It is of course well known that the Northumbrian smallpipe as we have it today developed musically in the first decades of the nineteenth century, whereas the smallpipes slipped into obscurity in Scotland and by the middle of the century had declined virtually to extinction in the shadow of the "big brother" bagpipe of the Highlands, the piob mor of such distinctive and assertive character. This obscurity was so complete that in the twentieth century, it became difficult to glean any information about the playing of smallpipes in Scotland; their role, if it survived at all in a musical and social sense, had been usurped by the “miniature pipes" - an inadequate, scaled-down version of the Highland bagpipe; worst of all, the musical repertoire, the style of fingering and the making of reeds for this tiny instrument of the bagpipe family had been lost and generally forgotten. These bagpipes had mostly been hidden away in the backs of cupboards or they had found their way, as curiosities of a former age, into museums where they would lie dead and silent in display cases; most importantly for the student of bagpipe history, they were inadequately documented or not documented at all.

There are four complete sets of smallpipes in the collections of the National Museums of Scotland and a generous quantity of discarded parts from broken and now for the most part lost sets. If it is not imposing a false categorisation on these instruments, the claim has always been made in museum registration and cataloguing that these are “Scottish smallpipes" or "Scottish chamber bagpipes"; their provenance and past history in every case are locatable at least in Scotland, and in one or two rare cases the names of bagpipe makers in Glasgow and Edinburgh are imprinted on them. The "signing" of these instruments is almost unknown before the nineteenth century and this absence of evidence is a sad feature for those trying to unravel the past history of the piping tradition of the British Isles.

In this typical situation of an instrument having no indication of who made it, it is always difficult to locate it in time and place until enough evidence has otherwise been amassed from styles of old instruments and fugitive documentary references. A set of smallpipes in the collection of the Scottish United Services Museum in the National Museums of Scotland may be said to be of vital importance in this respect. Indeed, it may be said to be almost a Rosetta Stone of Scottish bagpipe musicology, insofar as it is clearly early in the style of its manufacture, and bears an inscription which, assuming it to be contemporary, allows us to date the instrument with more precision than is usual with early surviving sets of pipes.

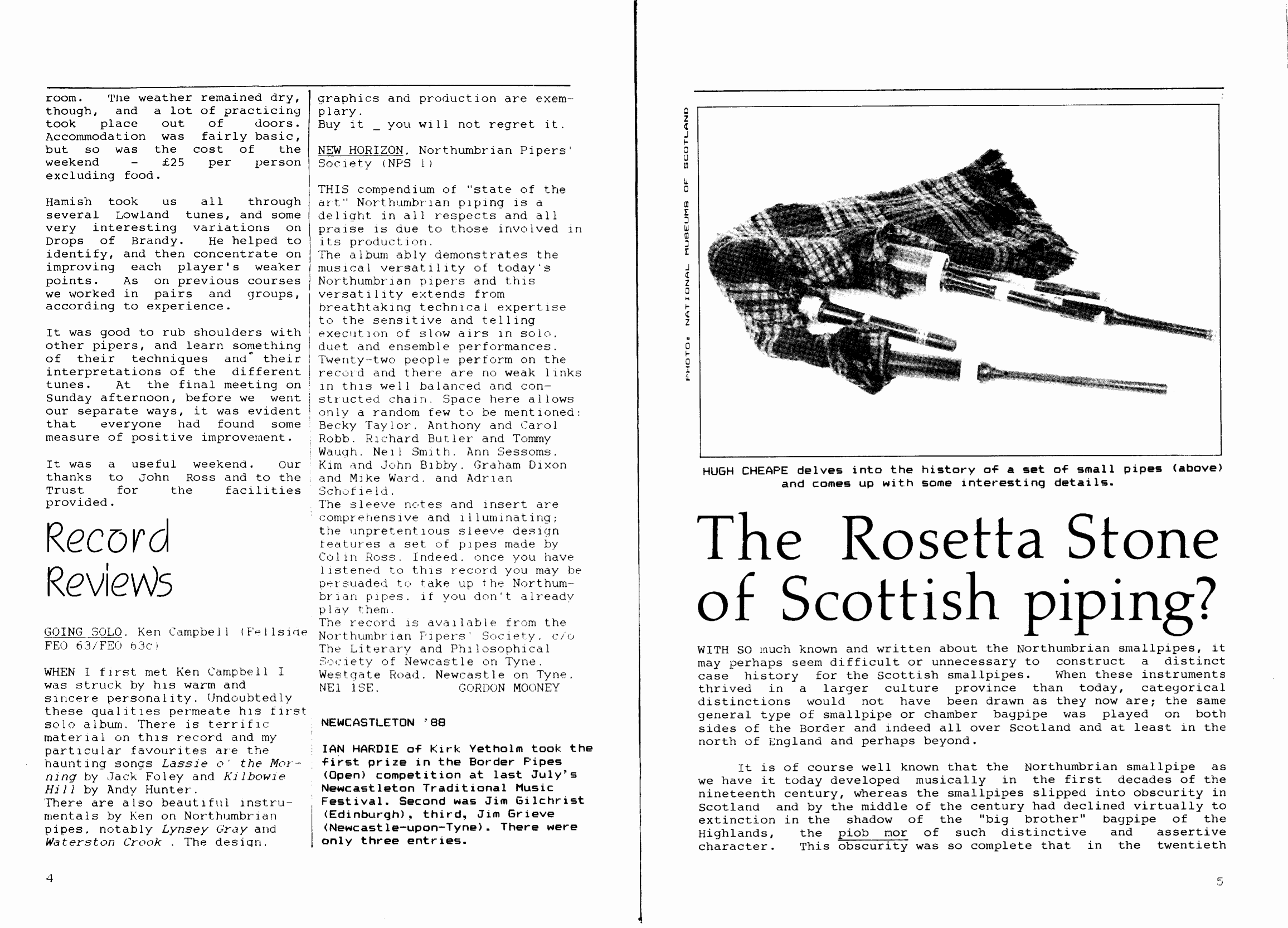

This bagpipe comprises a set of smallpipes with three drones set in a common stock. They have been assembled from a variety of woods such as ebony, rosewood and laburnum, and mounted with bone and ivory. The pipes are mouth-blown but the components as they have survived suggest that the pipes may have been bellows-blown or at least that the blowpipe has been a later addition to the set. This is a not uncommon feature in that the mouthpiece and blowstick are subjected to a great deal of physical pressure, break in the natural course of use and have to be replaced.The length of the chanter is 198mm and the cylindrical internal bore diameter of other early surviving smallpipe chanters. Two points of significance maybe inferred from this and other similar chanters; in the first place, the similarity in the size of bore and the sounding length being so closely comparable suggests that these pipes may have all been made to play in a set pitch; secondly, the very small, almost miniature, style of all these chanters brings the finger holes so close as to dictate a different style of playing with the tips or first joints of the fingers; this is of course more or less the style employed on the Northumbrian pipes, although the fingerhole spacing is not now so close on nineteenth and twentieth century smallpipe chanters. Given the predominance of the Highland bagpipe style of playing and fingering, this eighteenth century style of close fingering is now quite unknown in Scotland.

The three drones are tuned to the tonic, an octave below and the fifth between. The bass drone, with two joints, is 287mm long, the lower joint having been broken and subsequently repaired with a white metal sleeve. There is a "baritone" drone 178mm long with two joints, and a tenor drone 149mm long, also with two joints. The latter includes a tiny single reed, 46mm long, tuned with a small drop of wax on the tongue. The drones and stock are made from different woods, the bass and baritone drone possibly being of ebony and the tenor drone and stock possibly being of laburnum. The style of turning, the decoration on the joints, and the size and profile of the mounts are all closely comparable with other surviving small-pipes of, we presume, eighteenth or early nineteenth century date. The pipes have a sheepskin bag, cut to give a square outline and sewn with an intricate double welt.

The remarkable detail of this set of pipes is the inscription on an ivory ring mount of the drone stock and a shorter inscription on an ivory mount on the blowstick stock. They read:

"HONL. COLL. MONTGOMERY 1ST HIGHLAND BATTN. JANWY. 4 1757" and

“COLL. MONTGOMERY".

It is open to dispute that these inscriptions would have heen retrospective, dating perhaps to the time of disbandment of "Col. Montgomery's Highland Battalion", when a dedicated regimental musician may have recorded the history of his unit in an inscription on his smallpipes. Let us assume, for the sake of argument, that the inscriptions are more or less contemporary with the date recorded and that the pipes themselves, therefore, pre-date the inscription; this makes the instrument a comparatively rare survival of the mid-eighteenth century.

The historical information which the pipes bear so succinctly indicates a man of aristocratic background, an army unit or Highland regiment, and a precise date. This sort of detail is so rare as to be exceptional, and behind it lies a collection of historical facts of some significance. The name Montgomery or Montgomerie (it has been variously spelt) belongs to south west Scotland, and the prefix “Honourable" links it to the Montgomeries of Eglintoun. It was one of the Montgomeries of Eglintoun who was responsible for raising a Regiment for service in the Seven Years War that raged over different theatres of war in Europe and America between 1756 and 1763.

Col. the Hon. Archibald Montgomerie (1726-1796), who raised the 77th Regiment, Montgomerie’s

Highlanders, for service in America during the Seven Years’ War.

Using the biographical information in Sir James Balfour Paul's The Scots Peerage, we find that Hon. Archibald Montgomerie, the Col. Montgomerie of the inscription, was born in May 1726. He was the younger brother of Alexander, 10th Earl of Eglintoun, who subsequently and unexpectedly succeeded his brother as 11th Earl in October 1769. The former Earl, who was then at the peak of a prominent career in parliamentary and public affairs in Westminster, and agricultural improvement and estate management in Ayrshire, died as the result of being shot by an exciseman, Mungo Campbell, whom he had challenged for using a gun to poach on his lands at Ardrossan.This incident, which shocked the community, was woven into Galt's novel Annals of the Parish. John Galt (1779-1839), our remarkable early nineteenth century novelist, was born almost ten years after this act of homicide, but doubtless inherited enough information and chatter about it to use it, albeit anachronistically,in his "theoretical history" of the Ayrshire countryside in the later eighteenth century narrated through the persona of the parish minister, Rev Micah Balwhidder, in his own inimitable and idiosyncratic style. In this account, Eglintoun is thinly veiled as "Eaglesham" and the perpetrator as “Mungo Argyll". The shooting and the Earl's death are described in the context of his Lordship's worldly failings in such a way as to suggest the workings of Divine will and Judgement. The Earl and his family are used in the book not so much as personalities but rather as symbols of landed influence and power which, in the context of mid- eighteenth century Scotland, they incontestably were. Interesting as this is in throwing light on the Montgomeries of Eglintoun, it does not help us further in investigating the small-pipes and their historical context.

Before this fatal incident, Archibald and his elder brother, Alexander, having attended the Grammer School at Irvine, were then sent to England according to the fashion of the time to finish their education, the former to Eton and the latter to Winchester. After studying abroad for a short time he entered the army, receiving a commission in the Scots Greys in 1744. Archibald Montgomerie's military career is beyond the scope of this investigation until the outbreak of the Seven Years War in 1756.

The Seven Years War, against France which was fought with bitterness and ruthlessness in North America, is important for our purposes because it went some way to reversing eighteenth century prejudices against the Scots and particularly the Highlanders. Contributing to a growing trend of emigration, the Highlanders were lured over the Atlantic because they were considered to be hardy and able colonists. For better or worse, they became the first building blocks of a new British Empire. With the onset of hostilities between Britain and France, their competing colonial interests on the American continent made it one of the main battlegrounds. It became an attractive enterprise for “soldiers of fortune" and it is said that up to twelve thousand Highlanders may have enlisted for the war. Many of them accepted grants of land in Canada in return for their war service, and remained and settled there.

Some politicians - prominent among them William Pitt, later the Earl of Chatham, George II's prime minister - regarded the employment of Highlanders in the army as a means of destroying “disaffection” towards the government; his argument was persuasive and, looking back ten years later on his own initiative, he was to say:

"I have no local attachments; it is indifferent to me whether a man was rocked in his cradle on this side or that side of the Tweed. I sought for merit wherever it was to be found. It is my boast that I was the first minister who looked for it, and I found it in the mountains of the north. I called it forth and drew it into your service, an hardy and intrepid race of men..."

Two men were commissioned to raise regiments in the Highlands, Archibald Montgomerie and Simon Fraser, formerly the Master of Lovat. Two factors suited Montgomerie for the job; on the one hand, he was a man of cheerful, sociable and high-spirited character, and on the other hand, he was well-connected - the brother-in-law of Sir Alexander MacDonald of Sleat and also of Moray of Abercairney. The account of events surrounding Montgomerie's commission are given by the well-informed and sympathetic Col. David Stewart of Garth in his Sketches of the Character, Manners and Present State of the Highlander of Scotland published in 1822. It appears that all later accounts of Montgomerie's Highlanders are based on this text. Recruitment for the new regiment was apparently rapid and successful, and 13 companies were formed with the remarkable total complement of 1468 men. The Highland corps was numbered as the "77th Regiment". Col. Montgomerie's commission was dated 4 January 1757, the precise commemorative date inscribed on the set of smallpipes. The Regiment was formally enrolled at Stirling and rapidly embarked at Greenock for Halifax, Nova Scotia, together with the 78th Regiment or Fraser's Highlanders, Montgomerie accompanied his regiment to America where he served with one of the heroes of the War, General Amherst, in the campaigns especially against the Cherokee Indians. These campaigns were ruthless and bloody and the conventions of war and gentlemanly or chivalric behaviour were all forgotten.

Col. Montgomerie later became a member of parliament in 1761 and remained in the House of Commons until 1768. He also held a number of public honorary posts such as Governor of Dumbarton Castle and Edinburgh Castle and Deputy Ranger of Hyder Park and St James' Park. He was given the rank of General in 1793 and died at Eglintoun Castle in October 1796 aged 73. All this detail concerning a military career fails, perhaps, to throw much light on the smallpipes themselves but we may be turning our back on the obvious. Today, we tend to equate the smallpipes with a different social context from the military, and it may be difficult to envisage that this set of small-pipes had any direct connection with Montgomerie's Highlanders and their vigorous war service overseas. However, it is a remarkable statistic which Stewart of Garth records that when “Montgomerie's Highlanders" were enrolled there were thirty pipers and drummers on the strength, and this at a time when the proscriptive legislation against things Highland was still in force. An article in the Piping Times in 1986 (vol 38 page 52-53) has shown that one of the Skye family of MacArthur hereditary pipers joined the Corps and there would undoubtedly have been an impressive range of talents among these thirty musicians.

It would seem reasonable to conclude that this set of smallpipes belonged to one of these pipers in “Montgomerie's Highlanders" rather than to Hon Archibald Montgomerie himself, that their owner, who recognised in his Commanding Officer a well-disposed companionin- arms and a patron, played them perhaps on mess-evenings, and that he was one of those who declined a land-grant in North America on the cessation of hostilities in 1763 and returned with his pipes to Scotland. They were given into the care of the Scottish United Services Museum in 1965 having belonged latterly to a Pipe Major of the Tyneside Scottish in the Great War.

ENTERTAINMENT FOR SCOTTISH ASSEMBLY

The cross party campaign for a Scottish Assembly has been stepping up it’s efforts over the past year in making the issue of a Scottish Assembly a central one....not just in the political field, but in other fields of Scottish life, including cultural activities. Last year the campaign’s accelerated programme included setting underway an “Entertainment for an Assembly” campaign, canvassing entertainments of all types, folk, jazz and pop music, theatre, etc, to give some degree of commitment to a campaign, the ultimate aims of which should mean, among many things, more sympathetic attention being paid to arts in Scotland by a governing body located in Scotland.

In a circular letter to entertainers, Alan D. Armstrong, the campaign’s national convenor, explained: “Such commitment could involve related promotion or fund raising....It could be related to a specific performance or to one which is part of an arranged schedule......in any part of Scotland”.

The issue was raised at the AGM in October, and (see minutes), it was generally agreed that affiliation with the Campaign, (some other cultural bodies such as the Scots Language Society have become officially affiliated), would be putting the LBPS on an unsuitably political footing, but that the entertainment campaign should be mentioned in Common Stock for individual musicians to consider. Those who wish to give some commitment to the Campaign should contact the CSA’s National Secretary, Brian Duncan, 12 Regent Place, Edinburgh, EH7 5SB. 031 661 9150.