Hats off to Habbie Simson

>

By Jim Gilchrist, based on a talk he gave to the LBPS Collogue in Glasgow, a couple of years back ...

THE day daws. Imagine, if you will, a dawn chorus ... bird song ... a cock crowing ... the sounds of an early 17th-century village getting underway for the day. Somewhere among the cottages, a bagpipe strikes up with a reluctant, early morning groan, before levelling out, finding its pitch, and its music comes and goes about the lanes, fading and swelling, until a figure appears before us, from out of the mist. It’s a piper, playing a two-droned, mouth- blown bagpipe. He's not kilted, not even wearing a Tam o’ Shanter, but he is sporting a

wide-brimmed hat, decorated with flowers and feathers. Step forward Habbie Simson, piper of Kilbarchan ...

Habbie Simson lived, we are told, between 1550 and 1620, in the Renfrewshire village of Kilbarchan. Virtually all we know about his life, bar a little local lore, comes from a famous elegiac poem written after his death by one Robert Sempill (or Semple) of Beltrees, who lived from around 1595 to around 1665. Sempill was a local laird, the son of a courtier and theologian who also had a literary bent - this ran in the family. The Semple with whom we’re concerned went to Glasgow University, fought on the Royalist side during the Civil War, and wrote poetry ... and the poem for which he is almost solely remembered is The Life and Death of the Piper of Kilbarchan.

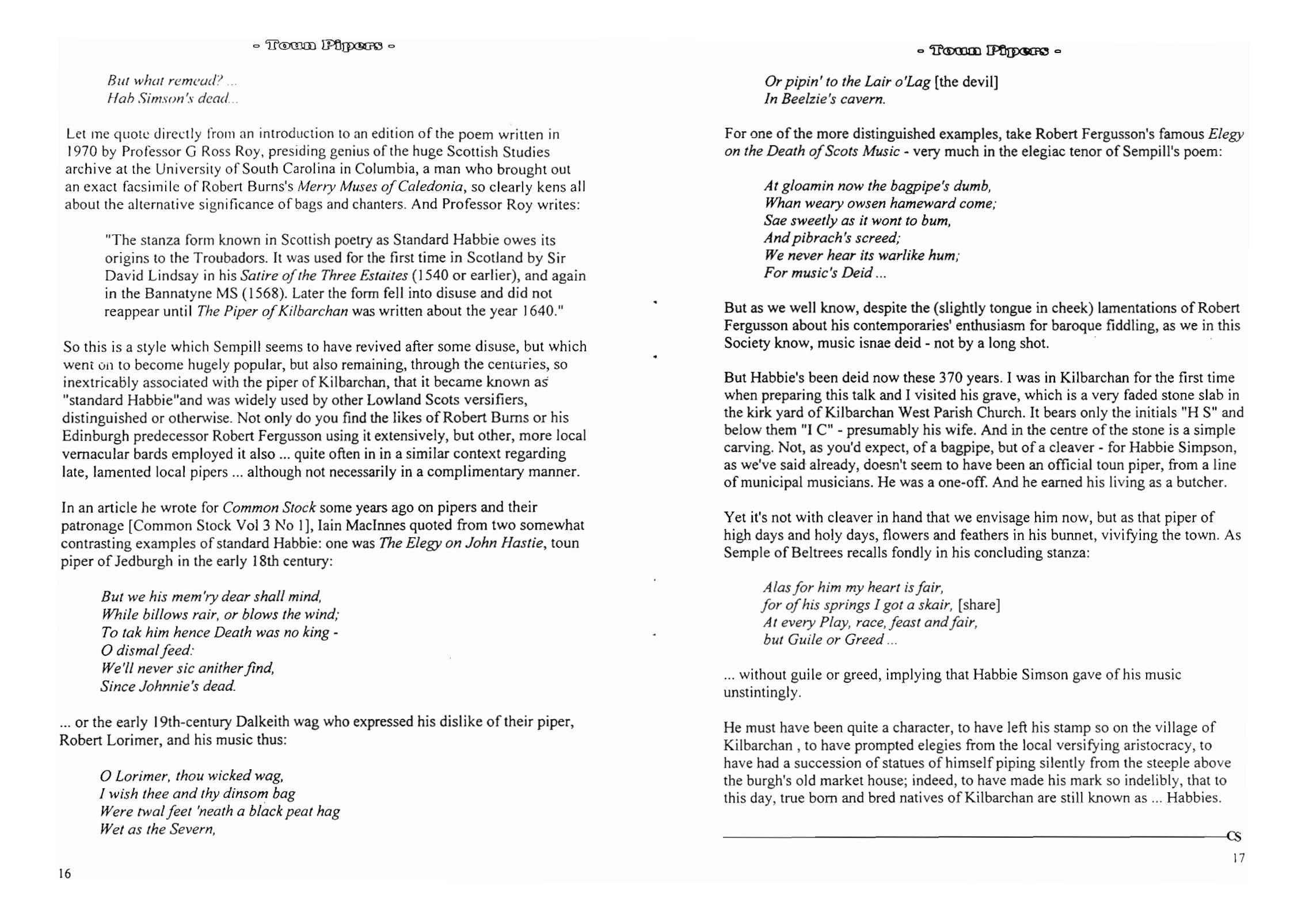

But Habbie Simson doesn’t only live on in the annals of this poem. So important has he be- come in the lore of Kilbarchan, that there have been successive statues erected to him on a building in the centre of the village known simply as The Steeple. Built in the 18th-century, perhaps an indication of this weaving and bleaching village’s increasing prosperity, The Steeple’s ground floor was a meal market. Later, until a few decades ago, it housed the local fire engine. Anyway, in a niche in the spire of The Steeple there stands a life-sized bronze statue of a piper - playing a two-droned bagpipe, and wearing that broad-brimmed hat.

According to a plaque below it, this statue was erected by public subscription to replace an early wooden effigy erected there in 1822. The timber statue was the work of a ship’s fig- urehead carver from Greenock named Robertson, who later moved down to Liverpool and made a reputation for himself there as a carver.

In his book Kilbarchan: A Parish History, written in 1902, the Reverend Robert Mackenzie refers to an oil painting of Habbie Simson which then was in the possession of a Mr James Caldwell of Paisley. The portrait, of unknown date - and I quote MacKenzie here - “represents the piper garishly decked in ribbons, flowers and feathers.” The sculptor Robertson is supposed to have to have referred to it when carving his statue.

I would hardly think this would be a contemporary portrait. I spoke to Paisley and John-

stone libraries about this and Paisley Museum, but none of them knew of the existence of such a portrait. But, just a couple of nights before I gave this talk, having been speaking to one or two people inolved in Kilbarchan Civic Society, I ended up phoning John Connel, the preses of the Kilbarchan General Society, which, I’m assured, is the oldest charitable institution in Scotland. And, oh yes, he knew about the portrait; at least he didn’t really know very much about it, but he knew exactly where it was - in one of the rooms of The Steeple, which is owned and used by the Society. There weren’t any reproductions of it, and I haven’t had time since then to go and see it. But I do suggest that the LBPS organise a Saturday afternoon outing to visit the Steeple; we could hire one of the rooms there as an extremely appropriate venue for us to meet and play in, and of course view this intriguing portrait of Habbie Simson.

The best part of two decades ago, when the Temple record label released its excellent piping compilation A Controversy of Pipers, one of the various things the late Seamus MacNeill didn’t like, when he reviewed the album in Piping Times, was the cover illustration, by Glasgow musician and artist John Gahagan, which depicted no less than Habbie himself, but which drove poor Seamus to muttering about pipers dressed in their grannies’ bunnets.

But there’s no particular reason to regard as improbable these images of Habbie Simson decked out in flowers and feathers. Sempill’s poem refers to him playing at St Barchan’s feast - St Barchan being the local saint (the name Kilbarchan - Kil Barchan, cell of Bar- chan). Now the old, pagan festival of Beltane became St Barchan’s feast - although the poet does seem to separate the two, refering to “Beltan and St Barchan’s Feast”. And St Bar- chan’s feast in turn became a local festivity called Lilias Day, named apparently after a local laird’s daughter - the daughter, in fact, of one of the Cunninghams of Craigend, with whom Habbie may have been in service at some point. And on Lilias Day they used to decorate the streets of Kilbarchan with flowers and heather. The festival seems to have lapsed early this century, but was revived in the Nineteen Thirties and again in the Sixties, and is still going.

In a Lilias Day programme from 1933, you find the line from a local anthem:

Sae here’s tae St Barchan, We're proud o’ his name.

An’ here’s tae the piper wha piped us tae fame.

So, Habbie Simson clearly means something to the people of this village, which by 1836 boasted some 800 looms and where, incidentally, you can still see the last Kilbarchan weaver’s cottage, and his loom, as preserved by the National Trust for Scotland.

The Reverend MacKenzie in his history doesn't really tell us too much about Habbie Simson, but he does give us one or two points of interest. He says there’s a tale that Habbie and his wife each reported the other’s death to the Laird and Lady of Johnstone, respec- tively, both gaining some money through sympathy for this non-existent tragedy, and, later on, he writes “both being caught red- handed while enjoying the fruits of their roguery”.

One thing that MacKenzie does say is that Habbie seems to have been a one-off, rather than one of a succession of municipal pipers in the village. He writes: “Neither are there good grounds for maintaining that Habbie... had an official appointment as a piper, with a salary of five merks, free occupancy of a piper’s croft and a suit of livery per annum. In Habbie’s case, the office began and ended with his occupancy.”

But one final tantalising piece of lore that the Reverend gives us, is that Habbie Simson is supposed to have engaged in a piping competition with one Rab the Ranter ... Now those of you who know the old song Maggie Lauder will know fine who Rab the Ranter was :

1 am a piper tae my trade, my name is Rab the Ranter.

The lassies loup gin they were daft when I blow up my chanter.

And in the last verse of Maggie Lauder, the young lady, having been shown a good time by Rab, comments: “There’s nane in Scotland plays sae weel since we lost Habbie Simson.”

Yet here’s Rab and Habbie having a piping stand-off. One gets the impression that the Rev- erend MacKenzie wasn’t much of a piping fan; his tone is somewhat sarcastic as he writes: “There is no information as to the basis on which superiority was to be determined - whether mere lung power, or extent of repertoire, or excellence of musical rendering” - nor as to the result. There may be more of a literary connection here, though, because one of Robert Sempill’s sons, Francis, is often credited with having written Maggie Lauder. One could go on and on exploring these connections ...

Robert Sempill’s elegy on Habbie, however, has much more interesting details to offer. So let’s turn to the poem. You can look at it from at least two points of view: firstly, from that of a piping enthusiast, wondering what sort of repertoire an early 17th-century Lowland village piper had - and the poem duly tells us that Habbie Simson habitually played Trixie, The Maiden Trace, and Whip-meg-morum, as well as the of kind tunes Lowland or Border toun pipers commonly used to rouse the community in the morning - The Hunt’s Up and The Day it Daws, the latter perhaps better known as Hey Tuttie Tattie or, more latterly, Scots Wha’ Hae.

Or, secondly there's the point of view of the social historian, interested in the context within which Habbie functioned as a piper - and, again, the poem lets us know that he played on holy days such as Beltane and St Barchan’s feast.

Habbie, we learn, also played at horse races and in time of war or at the wappenshaws which every community was expected to carry out regularly to maintain its readiness for battle - he would “bend up the Brags of Weir”, the vauntings or braggings of war. And he’d bring in the bells at new year, play at sheep shearings - remembering again that Kilbarchan was a weaving village; where the sheep and its fleece were the life blood of the community.

Sempill also records Habbie Simson as playing the pipes at “clerk plays” - plays acted out by clerics or others, representing scriptural themes. I find this very interesting, given the traditional attitudes we usually see in kirk and burgh records, suggesting virtually open

warfare between kirk and piper. Also, it says, “on Sabbath days his cap was feddered” - feathered - which it goes on to consider as “a seemly weid” - an appropriate outfit, although it doesn’t go so far as to say whether he actually played on Sundays.

And Habbie, it seems, was in the wars, winning his pipes, as the makar tells us, “beside Borcheugh” - or as another edition of the poems says, “Barcleuch” and I simply haven’t managed to get to the bottom of who, what or where Borcheugh or Barcleuch was (possibly some battle or skirmish? Informed suggestions welcome). Anyway, Sempill is either being very ironic, or Habbie was a man of some mettle, rather than that semi-comic mould into which local minstrels often fall - such as the fiddler, Patie Bimie, who is said to have run all the way back to Edinburgh when invited to take part in the Battle of Bothwell Bridge in 1679. And Habbie was a great footballer - “At every game the Gree he wan” - the prize he won - “for pith and speed”.

So while Habbie could indeed be a figure of fun, playing the clown at weddings -

He bobbed aye behind folk’s backs And shook his heid...

he seems also to have been a bit of a hard man when need be. The poem suggests, rather ambiguously, that he once killed a man, and took the consequences, “And bure the Fead!”, accepted the ensuing feud, although Sempill goes on to say: “But yet the man wan hame be- fore him - And was not dead!” Which sounds like a situation not unlike Synge’s Playboy of the Western World, in which a feckless son thinks he’s murdered his father in an argument and goes on the run, gaining a certain kudos for his deed. I don’t know. I suppose we’ll never know the truth with Habbie.

So the poem The Life and Death of Habbie Simson documents to a certain and tantalising extent both the piper's world and his repertoire. But a third point of interest - and something that neither Sempill nor Simson could ever have appreciated - is the stanza form in which the elegy is couched, distinguished by those dangling fourth and last lines ...

But when remead?... Hab Simson's dead...

Let me quote directly from an introduction to an edition of the poem written in 1970 by Professor G Ross Roy, presiding genius of the huge Scottish Studies archive at the Univer- sity of South Carolina in Columbia, a man who brought out an exact facsimile of Robert Burns’s Merry Muses of Caledonia, so clearly kens all about the alternative significance of bags and chanters. And Professor Roy writes:

“The stanza form known in Scottish poetry as Standard Habbie owes its origins to the Troubadors. It was used for the first time in Scotland by Sir David Lindsay in his Satire of the Three Estaites (1540 or earlier), and again in the Bannatyne MS (1568). Later the form fell into disuse and did not reappear until The Piper of Kilbarchan was written about the year 1640.”

So this is a style which Sempill seems to have revived after some disuse, but which went on to become hugely popular, but also remaining, through the centuries, so inextricably associ- ated with the piper of Kilbarchan, that it became known as “standard Habbie” and was widely used by other Lowland Scots versifiers, distinguished or otherwise. Not only do you

find the likes of Robert Burns or his Edinburgh predecessor Robert Fergusson using it extensively, but other, more local vernacular bards employed it also ... quite often in in a similar context regarding late, lamented local pipers ... although not necessarily in a compli- mentary manner.

In an article he wrote for Common Stock some years ago on pipers and their patronage [Common Stock Vol 3 No 1], Iain MacInnes quoted from two somewhat contrasting exam- ples of standard Habbie: one was The Elegy on John Hastie, toun piper of Jedburgh in the early 18th century:

But we his mem’ry dear shall mind, While billows rair, or blows the wind; To tak him hence Death was no king - O dismal feed:

We’ll never sic anither find, Since Johnnie's dead.

... or the early 19th-century Dalkeith wag who expressed his dislike of their piper, Robert Lorimer, and his music thus:

O Lorimer, thou wicked wag,

I wish thee and thy dinsom bag

Were twal feet ‘neath a black peat hag Wet as the Severn,

Or pipin’ to the Lair o’Lag [the devil]

In Beelzie’s cavern.

For one of the more distinguished examples, take Robert Fergusson’s famous Elegy on the Death of Scots Music - very much in the elegiac tenor of Sempill’s poem:

At gloamin now the bagpipe’ dumb, Whan weary owsen homeward come; Sae sweetly as it wont to bum,

And pibrach’s screed;

We never hear its warlike hum; For music’s Deid...

But as we well know, despite the (slightly tongue in cheek) lamentations of Robert Fergus- son about his contemporaries’ enthusiasm for baroque fiddling, as we in this Society know, music isnae deid - not by a long shot.

But Habbie’s been deid now these 370 years. I was in Kilbarchan for the first time when preparing this talk and I visited his grave, which is a very faded stone slab in the kirk yard of Kilbarchan West Parish Church. It bears only the initials “H S” and below them “I C” - presumably his wife. And in the centre of the stone is a simple carving. Not, as you’d ex- pect, of a bagpipe, but of a cleaver - for Habbie Simpson, as we’ve said already, doesn’t seem to have been an official toun piper, from a line of municipal musicians. He was a one--off. And he earned his living as a butcher.

Yet it’s not with cleaver in hand that we envisage him now, but as that piper of high days and holy days, flowers and feathers in his bunnet, vivifying the town. As Semple of Beltrees recalls fondly in his concluding stanza:

Alas for him my heart is fair,

for of his springs I got a skair, [share] At every Play, race, feast and fair, but Guile or Greed...

... without guile or greed, implying that Habbie Simson gave of his music unstintingly.

He must have been quite a character, to have left his stamp so on the village of Kilbarchan , to have prompted elegies from the local versifying aristocracy, to have had a succession of statues of himself piping silently from the steeple above the burgh’s old market house; indeed, to have made his mark so indelibly, that to this day, true born and bred natives of Kilbarchan are still known as ... Habbies.

Photograph of the statue of Habbie Simpson in Kilbarchan

Photo by Greenshed, Wikimedia Commons “I grant anyone the right to use this work for any purpose, without any conditions, unless such conditions are required by law.”