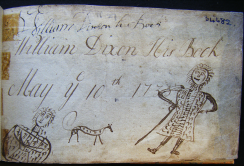

Callum Armstrong offers some new interpretations of this seminal document

I have been fascinated by the William Dixon Manuscript for a long time, and my interest was somewhat rekindled recently by watching Pete Stewart’s performances of some of the tunes on Facebook. I picked up Matt Seattle’s edition of the manuscript “The Master Piper; Nine notes that shook the world” and also a facsimile of the original manuscript. Here are two observations I made based on these two sources, influenced by my experience with early music.

Edward the Second.

Firstly, I believe the tune “Edward the Second” perhaps backs up the case for the William Dixon Manuscript being written for a bagpipe.

I would speculate that this minuet was not originally written for a diatonic bagpipe, but has been adjusted to form a diatonic tune. I assume this has been done by removing G sharps and a lone D sharp at the end of the A-part. I reached this conclusion because this creates a transient modulation: By adding a D sharp to the penultimate bar of the A-part, you outline a chord of B leading from A major to E major. This is a common 18th century trick, used not only in classical music but also in English folk tunes. Since I assumed that this piece’s harmonic framework is more of a classical one, we also need to add G sharps, in order that the dominant chord E is a major chord. In my opinion these changes make the tune more enjoyable to listen to.

Figure 1 shows a copy of “Edward the Second” with a basic baroque chord scheme and added accidentals where I think they could have been originally placed, thus keeping the tune more in accordance with the harmonic style of other minuets of the period.

The Lads of Alnwick.

Okay, now for the controversial bit. I would like to propose the question: Was the tune “The Lads of Alnwick” originally a 6/4 tune rather than a 3/2 tune?

Before I share my thoughts on this question, here are two things I noticed in the original manuscript: (1) There are no time signatures at all. (2) With the exception of “The Lads of Alnwick” which is barred in six crotchets to the bar, all the other tunes that we perceive as 3/2 Hornpipes are actually barred in four crotchets to the bar.

Figure 1. Edward the Second with a basic baroque chord scheme and accidentals

Figure 2. “The Lads of Alnwick” with the original quaver tail notation.

These observations make it very tricky to know for sure what meter Dixon intended these tunes to be played in. By and large the 3/2 hornpipes in the Dixon Manuscript are very rhythmically ambiguous, they can easily alternate between 3/2 and 6/4. The greatest example for me being “The New Way to Morpeth”.

“The Lads of Alnwick” is no exception, working well played in both 6/4 or 3/2. It is interesting therefore, that in the original manuscript the A-part of the tune’s quaver tails are joined in two groups of six rather than three groups of four. This is implying, at least by modern standards, that this A-part is in 6/4 rather than 3/2. By the nature of their rhythms the B- and C-part are quite ambiguous. I have often found the C-part of this tune odd in 3/2 and personally prefer it in 6/4 rather than 3/2. However, the D- and E-parts revert back to a 3/2 style grouping of the note tails. Figure 2 shows a version of the tune with Dixon’s original quaver tail configurations.

This raises more questions: Why did he change the quaver tail groupings? Did he intend to change the meter mid tune? Assuming he even notated this tune, did Dixon just make a mistake in the A-part with the quaver tails, or did he make a mistake with the D- and E-part? The question I find perhaps even more interesting though is, did Dixon view “The Lads of Alnwick” somewhat differently from the other perceived 3/2 hornpipes? It appears odd to me that he has written the tune out uniquely in a 6/4-3/2-barred scheme rather than a 4/4-2/2 one.

If anyone has any thoughts on this matter, I am very happy to read of them.