In searching the works of Walter Scott for mention of tunes he would have been familiar with, I should not have been surprised to find the first tune mentioned in his fiction, which comes in his first published novel, ‘Waverley’, was one that may well have been as well known in 1746, when the story is set, as it was when the book was published, in 1814. Here’s the passage in which Scott refers to it:

"The Balllie started from his three-footed stool.... ; flung his best wig out of the window ... .; chucked his cap to the ceiling, caught it as it fell; whistled Tullochgorum; danced a Highland fling with inimitable grace and agility, and then threw himself exhausted into a chair, “1

Discovering this reference to the tune sent me back to the work Adam Sanderson was then completing, re-constituting the files of Common Stock. He had recently sent me the December 2004 issue that contains Keith Sanger’s article about Walter Geikie’s engraving, the text of which is re-visited in this issue p. 43. Adam had reviewed the images printed in that article and had been able to acquire high-resolution images of Geikie’s work together with permission from Museums Scotland to reproduce them. Geikie’s engraving is of great interest in being one of very few depictions of what appears to be a set of Lowland pipes being played in their social context (readers may recognise the piper as having been the business logo of a weel-kent pipemaker). Geikie must have witnessed the scene he depicts, even if he could not hear it (having been deaf since an early age) and it must have been in Edinburgh, where he lived all his life: it was probably done towards the end of his life, around 1830. It has to be said, nevertheless, that the pipes he depicts have some characteristics - the number of crudely-drawn drones, for instance (there appear to be five) and the chanter end - that are more suggestive of what at the time would have been termed ‘Irish pipes’ rather then Lowland pipes as we know them. (See also the ‘conundrum’ Sanger considers re left/right handedness p. 44.) That said the fact that he gave his engraving the title he did demonstrates that the tune itself was as familiar to those around him as it had been to Scott some 15 years earlier.

In fact, Tullochgorum must be one of the most widely published tunes in the Scottish fiddler's repertoire. I have seen around 50 different citations for its appearance in various sources and have seen at least 6 manuscript settings from the 18th and 19th centuries. With all this material you might think that there remains little to be said about the tune or its history. And yet, a study of its origins and history, if one exists, remains hidden.

meaning the blue/green knowe, is located to the north-east of Boat of Garten, Speyside, north of Aviemore. In the Aviemore section of his book Granton and the adjacent area – A Guide to Strathspey, Rev. Wm Reid wrote ‘We are now in the country of the Grants, celebrated in the well-known lines of Sir Alexander Boswell: (1775 – 1822):

‘Come the Grants of Tullochgorum, Wi’ their pipers gaun before ‘em, Proud the mothers are that bore ‘em. Fiddle fa fum ‘2

In the section on Abernethy, Reid adds ‘near here is to be found the farm-house of Tullochgorm, and the well-known reel of that name will doubtless occur to the reader. We may even state that here the peculiar class of music known as Strathspeys had its origin... A prominent sept of the clan Grant held Tullochgorm for many centuries, and we are inclined to think that it was under their fostering influence that the music referred to assumed shape and form.’

This is a notion that Keith Sanger added much detail to in an unpublished essay titled ‘Reeling Round Tullochgorum’. Here Sanger described the payments made by generations of the Grant family during the 17th century to musicians, many of whom were violers; one of these payments was made ‘when the Laird was visiting Tullochgorum in 1638’. At least two recipients of these payments to violers were members of the Cummings family, hereditary pipers to the Laird of Grant, suggesting the likely exchange of repertoire between the pipes and the viol and by the early 1700’s the fiddle. All of which seems to confirm the Rev. Reid’s ‘inclination’, that it was in this manner and in this area that the 'Strathspey' as we know it first emerged.

Vile Italian tricks

So prominent is the tune in Scottish music’s Hall of Fame that it often figures in literary works which mourn the demise of ‘true’ Scottish tradition.

Words were set to it in 1776 by the Rev. John Skinner (1721-1807), pastor of the Episcopal Chapel at Langside near Peterhead. The third verse literally sings the praise of the tune:

There needsna be sae great a phrase

, Wi' dringing dull Italian lays,

I wadna' gi'e our ain Strathspeys,

For half a hundred score o' 'em.

They're douff and dowie at the best

Douff and dowie, douff and dwie,

They're douff and dowie at the best

Wi' a' their variorum:

They're douff and dowie at the best,

Their allegros and a' the rest,

They canna please a Highland taste,

Compar'd wi' Tullochgorum. … 3

However, Robert Fergusson (1750-1774) was the first to make the point: his poem ‘The Daft Days’ (in Scotland the 'daft days' are the Christmas/New Years holiday period) includes the following excerpt:'

Fiddlers! your pins in temper fix

And roset weel your fiddlesticks;

But banish vile Italian tricks

Frae out your quorum;

Nor fortes wi' pianos mix

Gie's Tullochgorum.

The story becomes more complicated, however, when we look at Fergusson’s ‘Elegy on the Death of Scots Music’ in which he mourns the passing of one of the leading musicians of his time:

Macgibbon's gane! ah! waes my heart!

The man in Music maist expert,

Wha could sweet melody impart,

An' tune the reed,

Wi' sic a slee an' pawky art;

But now he's dead.

Now foreign sonnets bear the gree,

An' crabbit queer variety

O' sounds fresh sprung frae Italy,

A bastard breed!

Unlike that saft-tongu'd Melody

Whilk now lies dead.

Twenty years later Burns made a similar argument in his ‘Amang the Trees’, set to the tune ‘The King of France He Ran a Race’, which bears a vague similarity to Tullochgorum (see Oswald’s Caledonian Pocket Companion, Bk. 8)

In his 2016 publication Geordie Syme’s Paircel o Tunes, Matt Seattle suggests that “Skinner’s and Fergusson’s equally weel-kent lines hint at many of the seeming contradictions of Scottish culture in the 18th century and, by extension, of today: native versus foreign, Lowland versus Highland, Scots versus Gaelic, city versus country. But differences need not be conflicts, and Fergusson in particular is striking a pose for dramatic – and humorous – effect. He was a personal friend of the Italian opera singer Tenducci, and his overblown Elegy on the Death of Scots Music is written in praise of William McGibbon (1690–1756), that notable Scottish composer of minuets whose Scots tune settings were praised for their Italianate refinement.”

(Ed. Note that McGibbon died in 1756, when Fergusson was only 6 years old at most)

For evidence of MacGibbon’s taste for ‘Italian tricks’ we need look no further than the so-called ‘McGibbon Manuscript’ (probably dating from around 1760 or slightly earlier and apparently in the hand of an ageing David Young) which contains a good deal of McGibbon’s music; here is a brief excerpt which well demonstrates the breadth of musical interest displayed by Fergusson’s ‘expert’.

The Corn Bunting

Putting aside this conundrum, this McGibbon manuscript also happens to contain the earliest appearance I have seen of the Tullochgorum tune bearing the title ‘The Corn Bunting’. Surprisingly, perhaps, this turns out to be a set of six strains identical in all but a few bars to the earliest known appearance of Tullochgorum. These six strains are the first six, those that have six bars in the even-numbered strains of the setting in David Young’s manuscript written for the Duke of Perth in 1734. Here are the opening six strains from the section of the manuscript labelled A Selection of the Best Highland Reels.

" />

" />

The first six strains of Tullochgorum from David Young’s 1734 setting

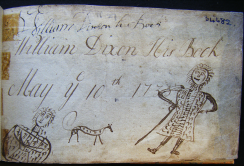

Since it seems certain that the same David Young wrote out this later manuscript, this might not seem so surprising, except for the new title. ‘The Corn Bunting’ Here is the title line of his later setting:

" />

" />

‘Some 70 years later, John Davie in his Caledonian Repository has the following:

" />

" />

Davie’s comment, that his tune is the ‘Original Tullochgorum’ and comes ‘from an old manuscript’ reveals its source in the fact that the second strain has six bars, something that is otherwise unique to David Young’s settings, in this case the later one. That Davie seems to have had access to this manuscript is further confirmed, since he also includes – on the pages before his ‘Tullochgorum’, ‘McGibbon’s graces’ for Corelli’s IXth Solo’ though he also prints the original air.

Davie’s collection was published around 1830, and seems to be recording an otherwise hidden tradition that links the Corn Bunting title to the Tullochgorum tune, a tradition which I have not seen noted elsewhere until Scot Skinner’s heroic 14 strain version dating from around 1900;4

[Ed: After the print issue of Common Stock was completed we learnt that Davie did indeed have access to this manuscript; a note in the opening page says that it was provided to him in 1837 by 'his friend Garnet Middleton': see https://hms.scot/manuscripts/sources/25/]

The only sighting of a tune with the title ‘The Corn Bunting’ without mention of a relationship with Tullochgorum is contained in the Guthrie manuscript, dating from around 1670. The notation in this manuscript long eluded scholars (and me) but has recently been ‘de-coded’ to be diatonic violin tablature on four-line staves, the top line being the lowest string, which explains why Glen described it as ‘accompaniments’ and declared that it contained ‘not one of the forty tunes supposed to be included in it’. A full transcription of the manuscript is due for publication in 2023 but Evelyn Stell included a transcription of the opening passage in her thesis:5

Here the tune appears to have the same harmonic structure (XYXX in Seattle’s notation) but as Matt has pointed out, it is in D and starts on the 5th, unlike all the Tullochgorum settings which start on the tonic or third and are almost always in G. Though at first 6/4 seems to be the most likely time signature, according to Aaron McGregor6 the manuscript contains marks that might indicate stressed notes and other features, and it is possible that it might be read as having minims for either the first or the third of each group of three, giving a 4/4 time.

" />

" />

‘The Corn Bunting’, from the Guthrie MS,1670-80

Whatever the reality of the connection, it re-surfaced again in 1900 in Scott Skinner’s manuscript copy of Tullochgorum. In the notes on the reverse of the sheet he writes:

“it is known to a few lovers of the strathspey as ‘The corn bunting’ ”

If this was so in 1900 it had long been only an aural tradition, since I have been unable to trace any source since Davie’s of a strathspey (or any other tune form) with that title in manuscript or publication. However, Scott Skinner’s notes also throw light on another possible origin of the Tullochgorum tune. A Mr A Toop supplied him with a rough notation for the tune ‘Jockey’s Fou and Jenny’s Fain’.

Jockey’s FowIn his notes to the Rev. Skinner’s song added to the version he included in his Songs of Scotland, Graham says ‘the composer of this tune is not known. Mr Stenhouse says it is derived from an old Scottish song tune, printed in Craig’s Collection in 1730.8

What Stenhouse wrote was ‘I have never been able to discover who framed the reel of Tullochgorum but the composer has evidently taken the subject of it from the old Scottish song tune ‘Jockey’s Fow and Jenny’s Fain’. The version he prints is clearly the source for the version that appears, roughly hand-written, in Scott Skinner’s note.

" />

" />

Whilst at first it appears similar, closer examination leads to doubts; this piece is definitely in G major with standard harmonic cadences in D and C, whereas Tullochgorum is defiantly in what is described as ‘double-tonic’ mode, the second ‘tonic’ (the ‘Y’ in Matt’s notation) is consistently the F below. If these two tunes are connected, then it would be tempting to see Tullochgorum as the source of this one, rather than vice versa. Nevertheless, Ramsay’s verses were published in 1723 and although he re-wrote all but the first verse, it was by that time an old song.

The two tunes are sufficiently similar to assume that they share a common origin; Perhaps Craig ‘civilized’ Tullochgorum in the same way Ramsay did for the words or perhaps Tullchgorum was an adaptation of Jocky’s Fu for the bagpipes. David Young included a setting of Jocky’s Fou in his MacFarlane manuscript, 1740:9

The first printed appearance of Tullochgorum is in Bremner’s 1757 collection, the bare bones of Young’s tune:

" />

" />

Tulloch Gorm, from Robert Bremner’s A Collection of Scots Reels etc., 1757

In his book of Geordie Syme’s tunes Matt Seattle has included a setting very similar to this from a manuscript in the NLS (NLS Ing 153, after 1762?) and has pointed out a feature of a number of these settings, the introduction of one note above the octave. In all other senses these basic settings could be as much standard pipe tunes as fiddle tunes, after a suitable transposition.

It must have been around the time of Bremner’s publication that David Young was preparing the McGibbon Manuscript, probably the last time the tune appears in any other form than a strathspey, except for James Aird’s setting in his first book, from around 1782: Aird’s setting is unusual in being in D, otherwise it is identical to Bremner’s (with the omission of the dotted quaver in bar 7):

"/>

"/>

Tulloch Gorm from Aird’s ‘Airs’, 1782

The earliest setting I have seen in which Tullochgorum has become a strathspey is that published the same year as Aird’s by Angus Cumming: in his A Collection of Strathspey or old Highland Reels, 1782:

" />

" />

Angus Cumming: in his A Collection of Strathspeys, or old Highland Reels, 1782

[Ed: After the print edition was published, Keith Sanger sent us details of the accounts for Cumming's book showing that it had been ready for printing in 1775; the above is from the 2nd edition 1782: the first edition, finally printed in 1780, was titled 'A Collection of Strathspey or old Highland Reels', a subtle difference]

When Burns was visiting Dunkeld he was fortunagte enough to meet up with a Dr Peter Stewart, ‘an enthusiastic violin player’, who introduced him to Neil Gow “The greeting was a cordial one on both sides, …The magician of the bow gave them a selection of north-country airs mostly of his own spirited composition. "Tullochgorum" was also duly honoured,”

" />

" />

Collection of Strathspey Reels, Neil Gow, 1784

By this time the tune had become known in Northumberland (and probably elsewhere in England); there is a simple setting in William Vickers’ 1776 manuscript (with a new alternative title) and Peacock included 4 strains in his 1805 collection of tunes ‘adapted for the Northumberland smallpipes’. Both of these Northumbrian settings retain the tune’s ‘reel’ nature:10

" />

" />

From William Vickers MS 1776 (courtesy of the Folk Archive Resource North East) " />

" />

From Peacock’s Favorite collection of tunes etc, 1805

Among the earliest Highland bagpipe settings is that in Donald McDonald’s A Collection of Piobaireachd, 1822 p. 6 (note the high g# as the penultimate note):

" />

" />

A Collection of Piobaireachd, Donald McDonald, 1822

Numerous versions were printed throughout the 19th century, in both fiddle and pipe settings, until James Scott Skinner produced his monumental 14 strain version in 1900. He also wrote three notes around the title at the top of the manuscript of the basic tune (with chords), which he gives as “Strathspey - Tullochgorum =”. To the left of this he writes ‘Dorian Mode / Flat 7th’; above the title he writes “The Corn Bunting The Dark blue Hill” and to the right, ‘Very Old/ composer MacPherson / 17th century'. The ‘dorian mode’ is an error, of course - for that to be true the thirds (‘B’) would have to be flat; the mode is mixolydian, and Skinner gives a ‘natural’ sign in the f line as the key-signature. As to who this MacPherson was, and where Skinner acquired this information-both remain a mystery.11

" />

" />

Natalie MacMasters gives a spirited performance of Skinner’s setting on youtube; Whether Skinner would have approved is another matter.12

Notes

1 .Scott, Walter, Waverley, 1814, chptr 37

2. Reid, Rev. Wm. Granton and the adjacent area – A Guide to Strathspey, p. 45ff

3. Graham, G. F., The Songs of Scotland, 1887 4. Scott Skinner’s setting and the notes accompanying it are online at https://www.abdn.ac.uk/scottskinner/display.php?ID=JSS0094 It’s tempting to see the ‘Corn Bunting’ connection as an Aberdeenshire tradition.

5. Stell, Evelyn, Sources of Scottish Instrumental Music 1603-1707, thesis available online athttps://theses.gla.ac.uk/76280/

6. Aaron McGregor’s comments on the Guthrie MS are at https://hms.scot/manuscripts/sources/6/

7. https://www.abdn.ac.uk/scottskinner/display.php?ID=JSS0096

8. Stenhouse, William, Illustrations of the lyric poetry and music of Scotland, 1853

9. ‘A Collection of Scotch Airs With the latest Variations. Written for the use of Walter Mcfarl[an] of that [Ilk]’. The transcription is from Ronald MacDonald’s website https://rmacd.com/music/macfarlane-manuscript/collection/

10. Thanks to Matt Seattle for pointing me to the example from Peacock

11. https://www.abdn.ac.uk/scottskinner/display.php?ID=JSS0095

12. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Sdc-oL6VjIc

" />

" />