Matt Seattle identifies another ‘standard’ Scots verse-form

This issue of Common Stock contains yet another elegy upon a deceased piper in the verse form which Allan Ramsay named “Standard Habbie” after Robert Sempill’s “Lament for Habbie Simpson; or, the Life and Death of the Piper of Kilbarchan”, and which later became known as the “Burns stanza” or “Scottish stanza”, even though it had previously been used in Provençal poems and miracle plays from the Middle Ages.

Your editor pointed out to me the obvious fact that, despite the number of elegies to pipers, the unevenness of the Habbie form does not lend itself to any of the metres used in Scottish traditional music. In contrast, there exists a truly native Scottish verse form which readily lends itself to the 9/8 (or 9/4) metre and which I shall call “Standard Willie” because its lyric and associated melody make a perfect fit and were, I surmise, made by one of our Border minstrels, either Rattlin Roarin Willie Henderson himself or another bard narrating his adventures and misadventures.

Although Robert Burns is now associated with Willie’s song, he was late to the party, adding just one stanza to the two which had come down to him, though that one stanza shows that he instinctively understood the music of the form better than the writer of the other two verses:

As I cam by Crochallan

I cannily keekit ben,

Rattlin, roarin Willie

Was sitting at yon boord-en’,

Sitting at yon boord-en’,

And amang guid companie;

Rattlin, roarin Willie

Ye’re welcome hame to me.

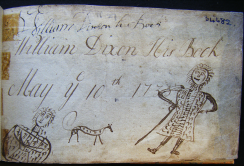

Each short line takes up one 9/8 bar, and the way the fourth line is repeated in the fifth is reflected in the melody, as in the first strain of William Dixon’s version:

Writing after Burns, Sir Walter Scott and Sir Walter Elliott of Wolfelee both gathered traditional verses which appear to be fragments of an earlier and longer narrative ballad. All four stanzas which Sir Walter Scott knew display the “mirroring” of lines 4 and 5; here is the last:

The lasses of Ousenam water

Are rugging and riving their hair,

And a’ for the sake of Willie,

His beauty was sae fair;

His beauty was sae fair,

And comely for to see,

And drink will be dear to Willie,

When sweet milk gars him die.

Allan Cunningham (The Songs of Scotland, Ancient and Modern, 1825) rewrote the narrative quoted by Scott, but only used the mirroring in the third of his four verses:

Now may the name of Elliot

Be cursed frae firth to firth! —

He has fettered the gude right hand

That keepit the land in mirth.

That keepit the land in mirth,

And charm’d maids’ hearts frae dool;

And sair will they want him, Willie,

When birks are bare at Yule.

Cunningham also had the nerve to imitate Burns’ song but, tellingly, totally ignored the mirroring. The last of his four stanzas runs:

As I came in by Crochallan

I cannilie keeket ben,

An’ Rattling Roaring Willie

Was sitting at our board en’,

An’ drawing his best bow-hand,

An’ drinking the wine sae free —

O Rattling Roaring Willie,

Ye’re welcome hame to me.

Four further songs or fragments are given by Sir Walter Elliott and W. Eliott Lockhart, who completed the article about Willie which was published in Berwickshire Naturalists’ Club, Transactions, Vol. 11, 1885-1886. In a crudely quantitative fashion, between them they comprise 23 complete stanzas and one half stanza. Of the 23, over half (13) contain mirrored lines.

Returning to Allan Ramsay (1686 – 1758) here is the first of three verses from his “To L. M. M. to the tune of Rantin roaring Willie.”

O MARY! thy graces and glances,

Thy smile so inchantingly gay,

And thoughts so divinely harmonious,

Clear wit and good humour display.

But say not thoul’t imitate angels,

Ought fairer, though scarcely, ah me!

Can be found equalizing they merit,

A match among mortals for thee.

Although Ramsay was perfectly able to write in Scots he also wrote in the Arcadian idiom; his second and third stanzas are equally tortuous, and while all three faithfully follow the 9/8 rhythm, none employ the mirroring technique.

We conclude this little exploration with the first stanza from Peggy by William Nicholson (1783–1849), “The Bard of Galloway”, to the tune he calls Swaggering, Roaring Willie.

When first I foregathered wi Peggy,

My Peggy and I were young;

Sae blythe at the bught i the gloamin

My Peggy and I hae sung.

My Peggy and I hae sung,

Till the stars did blink sae hie;

Come weel or come woe to the beggin,

My Peggie was dear to me.

William’s song fits the tune and maintains the mirroring in all his four verses.

While it is an easy observation to make that none of the foregoing examples are great poetry, the “Standard Willie” form, with its 9/8 rhythm and internal repetition, has both a musical quality and a narrative urgency of its own: perhaps it has yet to exhaust its potential?

[Footnote: my longer 2008 article contains fuller versions of most of the above lyrics and is currently still visible on he LBPS website; you can find it by using the ‘search’ menu and entering ‘rattlin roarin willie’ (in fact, just ‘willie’ will do).